Horses suffer back pain and this is well documented and recognised but quite difficult to diagnose as it often is hidden or accompanies other more obvious issues like hind leg lameness.

The spine is the central mechanical structure holding the majority of the heavy internal organs and digestive system, while carrying the cranial nerves along the spinal column and so sending both sensation and motor information to and from the brain. It’s connectivity to all parts of the horse is significant and it is both affected by and affects movement in the furthest points in the mouth and tail and feet!

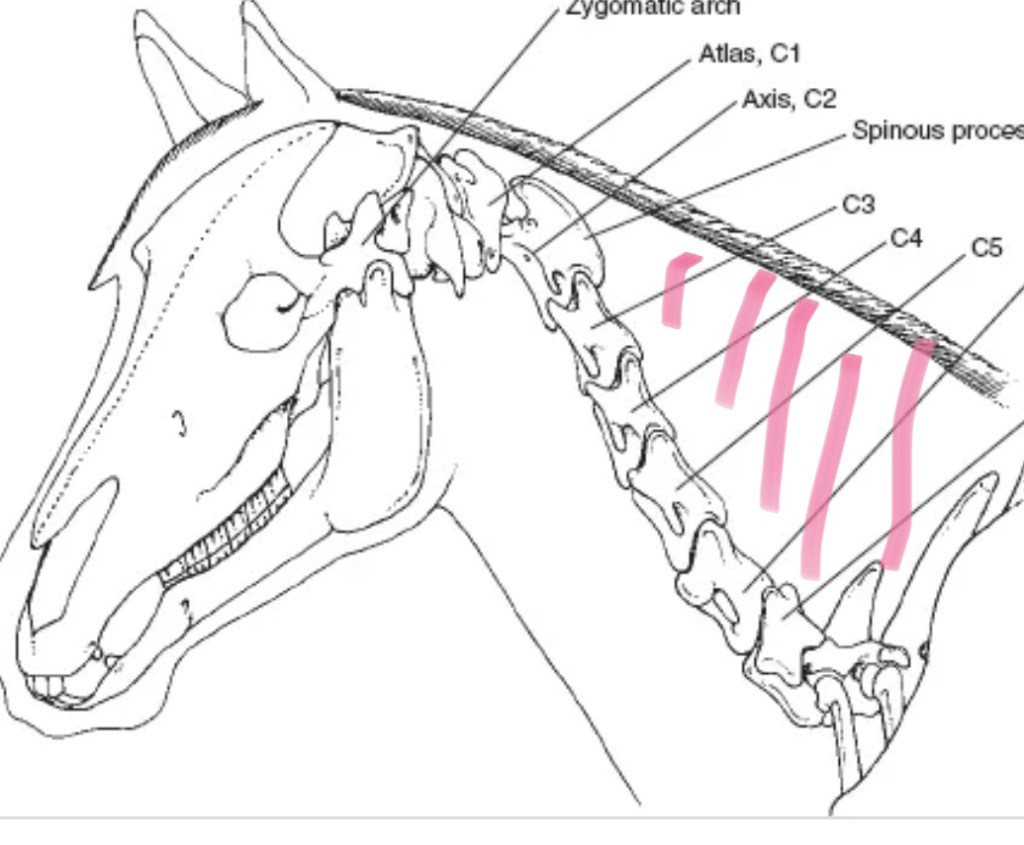

It consists of vertebrae buffered by discs of fluid filled cartilage and is held in place and manoeuvred by hundreds of ligaments, tendons and muscles as well as the fascia which holds the whole horse in tensegrity (see the last blog post on the bottom line for a brief definition). 1. Cervical vertebrae start behind the poll and run through the middle of the neck.

The reason these vertebrae are so low is because the head is heavy and horses need to be able to lift it so it is a mechanical engineering solution. The majority of what we see in the horse’s neck is the muscles needed to support this large heavy structure.

Most movement happens at the base of a horse’s neck. However, quite a lot of movement happens at the second vertebrae behind the skull too. This is what enables a horse to nod, and look left and right.

If the horse’s head is too high, the first vertebrae locks and they can’t flex left or right. The same happens if a horse over-flexes.

Next vertebrae are the thoracic, which start at the withers and connect to the ribcage. (You can feel the bony projections, which are called spiny processes, at the top of the horse’s back along the withers). The first three vertebrae are hidden under the shoulder. This area also consists of muscle to enable the head to lift, plus carry its weight and that of the neck.

The spinal cord runs along the bottom of these vertebrae which is deep within the horse, offering it considerable protection.

The lumbar vertebrae then run on from the thoracic vertebrae. The lumbar vertebrae stick out to the side, as well as the top, because they do not connect to any ribs. There is limited rotation or flexion between the lumbar vertebrae, because nodules hold them together and reduce the range of movement. It is also very important that the saddle doesn’t finish here, because that would cause a pressure point. The way to find the first lumbar vertebrate on your horse is to feel for the top of the last rib and run your finger up to the top. The lump you feel at the top is that first lumber vertebrae.

Next comes the sacrum. Spiny processes in the lumbar vertebrae face forward towards the head, whereas those in the sacrum face the tail. Consequently, there is a V shape where they meet. That is known as the lumbar/sacral junction, which is what enables a horse to bring its hindleg under its body. Flexion and extension happens at this junction — that is why a riding coach refers to a horse needing to lift its back. Unless it does, the range of movement in this area is restricted and the horse cannot engage its hindleg.

Next to this is the sacroiliac joint, where the sacrum vertebrae meet the ilial at the top of the pelvis. There is very little movement in the sacroiliac joint, whereas the lumbar/sacral junction moves a lot. (This is where the horse arches to urinate) That makes this a complex area and it’s why so many problems stem from here or result in a problem here.

There are between 18 and 22 tail vertebrae, which run to the end of the dock. The spinal cord stops after the sacrum, but muscle and ligament continues to the end of the dock. This means the tail can reveal a lot about the horse’s back.

For example, a horse who is clamping its tail down or holding it to the side probably has something going on elsewhere in the back. Make sure you are familiar with how your horse naturally holds his tail — any sudden change is an early sign that means you can get help before more serious damage is done.

The interconnectedness and centrality of the horses back is demonstrated well by looking at one of the many muscles in his back; The longissimus dorsi, is the main muscle in the horse’s back and runs deep underneath the saddle. However, it is not just local to this area. The longissimus dorsi starts at the 4th neck vertebrae and and attached into the sacrum in the hind quarters. Branches of the longissimus dorsi also connect to the head and tail. When you rub your horses back you typically feel the superficial muscles that go over the deep muscles like the longissimus.

Back pain is more challenging to diagnose than a lower limb issues due to the inability to palpate all the structures (we can’t get our hands inside the horse), reduced ability to use diagnostic imaging and differing sensitivity between animals. (Unfortunately some horses are excessively stoic when it comes to bodily pain and type of horse or character is no guide to that. Even those that are really quite expressive about a plastic bag waving in the wind can be utterly stoic when it comes to quite significant structural pain. I have an Andalusian /American Paint cross who is a drama queen about flowers and butterflies but who effectively hid his very squint pelvis and SI joint pain from us all for some time until a really good look with gait analysis technology and palpating demonstrated just how much discomfort he must have been holding when ridden).

Secondary back pain is much more common, although it can often be missed if treatment focuses on the primary problem.

Back pain tends to present as poor performance, and it can easily and accidentally be ignored when rehabbing the primary issue and particularly if that very rehab means the horse is working at a lower level than usual for a time.

It should be noted that when the veterinarian says that treatment is concluded they are often talking about the primary issue and that is not an instruction to go directly back to the usual level of work without having a good eye on the possibility of secondary pain in the back.

Imagine walking awkwardly for months due to a painful knee, then receiving treatment that removes that pain. It is highly likely that your compensatory pattern of movement will have created discomfort elsewhere in your body and usually in your back. Add to your problems a rucksack filled with puppies that you don’t wish to drop and that is sometimes balanced and sometimes not so much; you are going to have slightly poorer performance in you strident dance than you would have had prior to the knee issue – I know I’m labouring the point a bit but I see so much ‘fall out’ from owners misunderstanding of vets who do not intend to imply full function when they conclude treatment. This is no failure on the part of the veterinarian but perhaps an education failure on the part of those of us who attempt to teach riding and horse care that not all

owners and trainers understand the interconnectivity of the horses body and the healing processes that follow both injury and treatment.

So how is it that the back is so adversely affected by other problems in the horse (even including stomach problems like ulcers)? The back of the horse holds everything.

Imagine a suspension bridge with the towers being the horse’s legs and the roadway being the spine; everything that hangs under the roadway will be affected by and will affect the towers. If the weather bites away at one of the towers so that it changes it’s plain and maybe angles out or in a little, the structural integrity of the whole bridge will be put at risk. Now imagine one of those fantastic bridges that had a train running under and a roadway over. The pressures are greater still due to the weight (in our analogy a really long gut and big heavy organs) hanging under the bridge. Even if we mend the tower that was damaged, we would reasonably expect the bridge to remain closed to traffic and trains for a while until any structural problems above and below are mended. I probably took the analogy a little far but you get the idea. If the vet mends the tower – we still have the road and maybe the railway to rebuild.

We often see links to back pain in hind limb lameness. The lumbar region of the back, the sacroiliac joint, and the hock joints, with the proximal suspensory ligament, are four structures that often impact each other. Any imbalance caused by lameness will mean the forces exerted on and through the pelvis will be asymmetrical. The muscles along the spine bear this asymmetry and can respond by spasming, which creates a different pain cycle. The ‘twisting’ of the back that arises from a hind limb lameness causes the muscles in the back to become sore. I regularly see horses that have suspensory issues and present with little or no movement in the pelvis and a classic little dip in the muscle just in front of the SI joint suggesting a complication of their compensatory movements being something that has happened in the SI itself. With appropriate bodywork this can often be resolved and especially in cooperation with the farrier or hoof care provider but if left it will almost certainly develop into a job for our veterinary colleagues and can even result in permanent damage.

Bone spavin, arthritis in the hock, is a common hind limb lameness that culminates in a sore back. Because of the chronic progressive nature of this syndrome, the back is continually compromising for the hind limbs not weight-bearing evenly. The horse will start to shift his weight from the sore hind limb to the diagonal front limb, and in the process, the back muscles will tighten. As the muscles along the spine become sore and they can go into spasm. The muscles tighten and shorten, which adds to the asymmetry even more. This constant loop culminates in a worsening of clinical signs. Until the primary cause is found and treated and the clinical manifestations of the secondary back problem have been addressed and resolved, the horse will not be able to correct himself.

The feet are essential to assess when thinking about secondary back pain. If the horse is imbalanced in the foot, the back will compensate if the hoof is incorrectly balanced, e.g. low heel and long toe; the horse will alter the way it moves, putting strain on the back muscles.

Another area to consider is the head and mouth. In an earlier blog I talked about how they are connected via the bottom line to the back foot but they have another mechanical connection to the top line too in the interconnecting vertebrae and discs. If there is a pain in the mouth, the horse may raise or slightly angle his head and hollow his back to avoid contact with a bit or even to adjust his head while eating. This pain causes the spine to flex down toward the lower part of the horse, which abnormally pulls the muscles and makes it nigh on impossible to engage his abdominal muscles. The horse may also twist his head, causing his neck to rotate. This also adds stress and strain to the spinal column.

It is worth considering here how you feed your horse. In a future post I will look in more depth at feeding positions but bear in mind while eating at different heights (horses are browsers as well as grazers) is normal, tugging food out of tiny holes in slow feeder nets is not a normal action for the horse’s muscles and variety of feeding styles is probably not only the spice of life but the saving of necks and backs!

◦