SERRATUS VENTRALIS THORACIC (SVT)

The SVT is the second part of the Serratus Ventralis muscle.

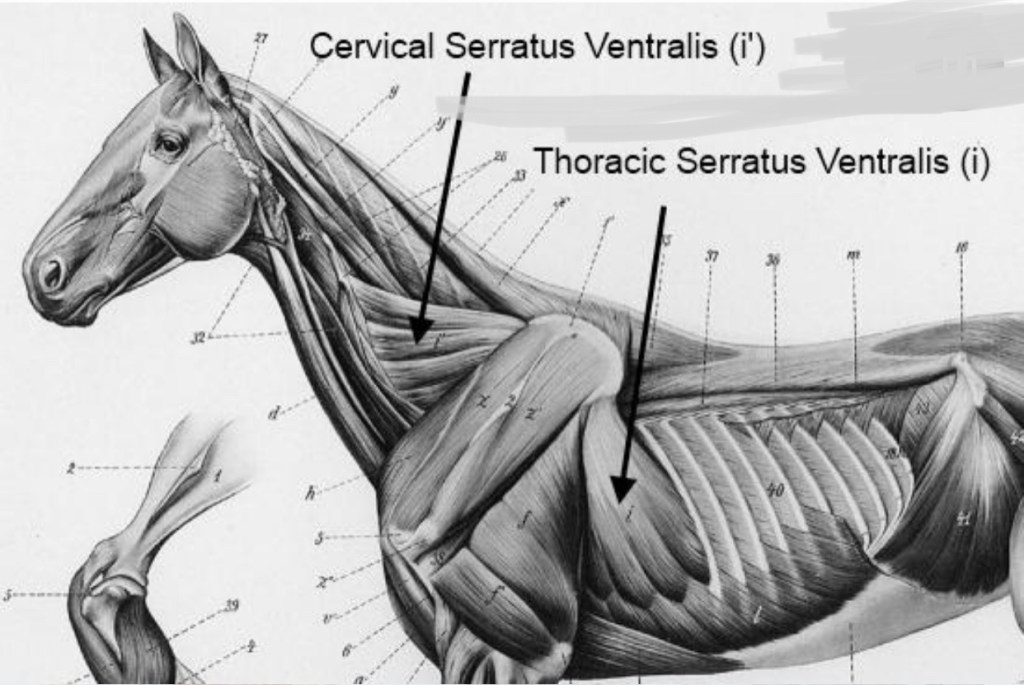

It is one of the deep muscles of the body and really essential to the horse’s movement. Serratus Ventralis is an essential muscle of the thoracic sling, supporting the weight of the neck and thorax from its position on the medial aspect of the scapula. This muscle is again divided into a cervical and thoracic portion, with the cervical portion originating on the transverse processes of C4-7 and the thoracic portion originating on the 1st to 8th ribs. Both portions insert on the medial aspect of the scapular cartilage and are innervated by the ventral branch of the local spinal nerve and the long thoracic nerve. The Serratus Ventralis Cervicis is much thicker than its thoracic counterpart. It extends along

the horse’s neck and draws the upper part of the shoulder blade forward. It can become hypertrophied or more pronounced in case of lower limb trauma, when extension of the front limb is diverted to the trunk muscles.

Indirectly, both serratus muscles are also very important for proper functioning of the horse’s stay apparatus as they aid in sustaining the horse’s weight when the muscle bulk relaxes. It should be considered in horses that do not appear rested that the stay apparatus and the thoracic sling apparatus should also be looked at in a wholistic diagnosis process.

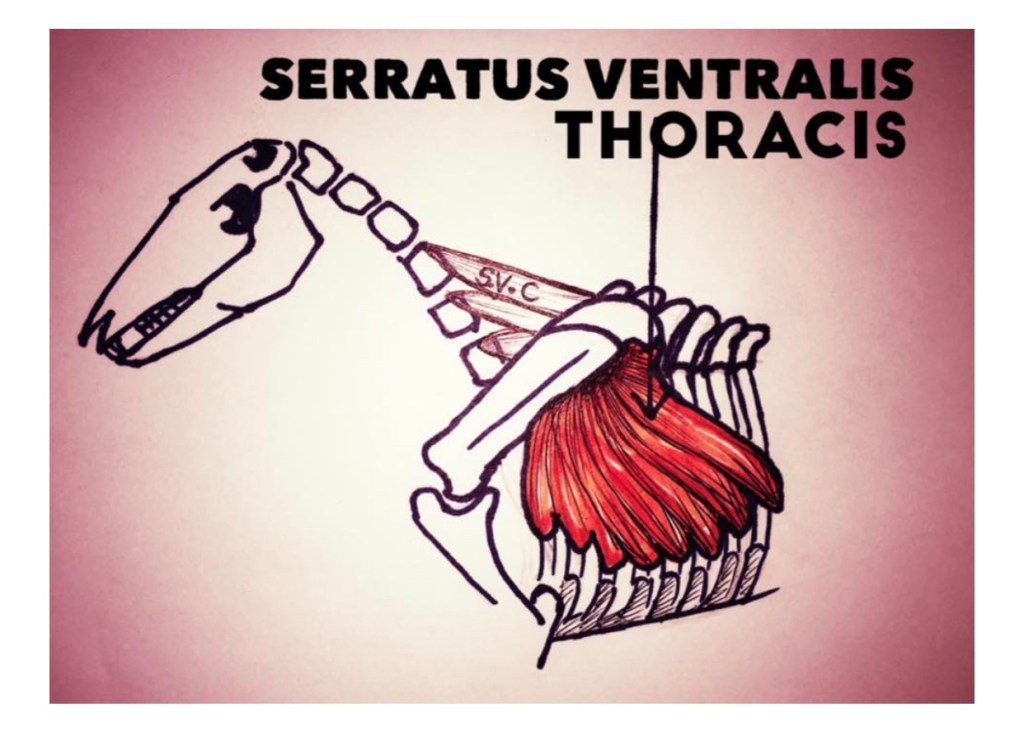

The serratus ventralis thoracic is the section of the muscle that is located behind the shoulder in the region of the thoracic vertebrae as the name would suggest.

The Serratus Ventralis Thoracis attaches the inside of the horse’s scapula to the ribcage and can be intimately linked to the External Oblique. It is linked to breathing functions because of its position.

It inserts into the shoulder blade and attaches into ribs 1-8/9.

(Ribs 1-8/9 ——> Medial Aspect of the scapula cartilage)

What does it do?

• Draws the the scapula (the shoulder blade down and back, playing a part in extending the limb.

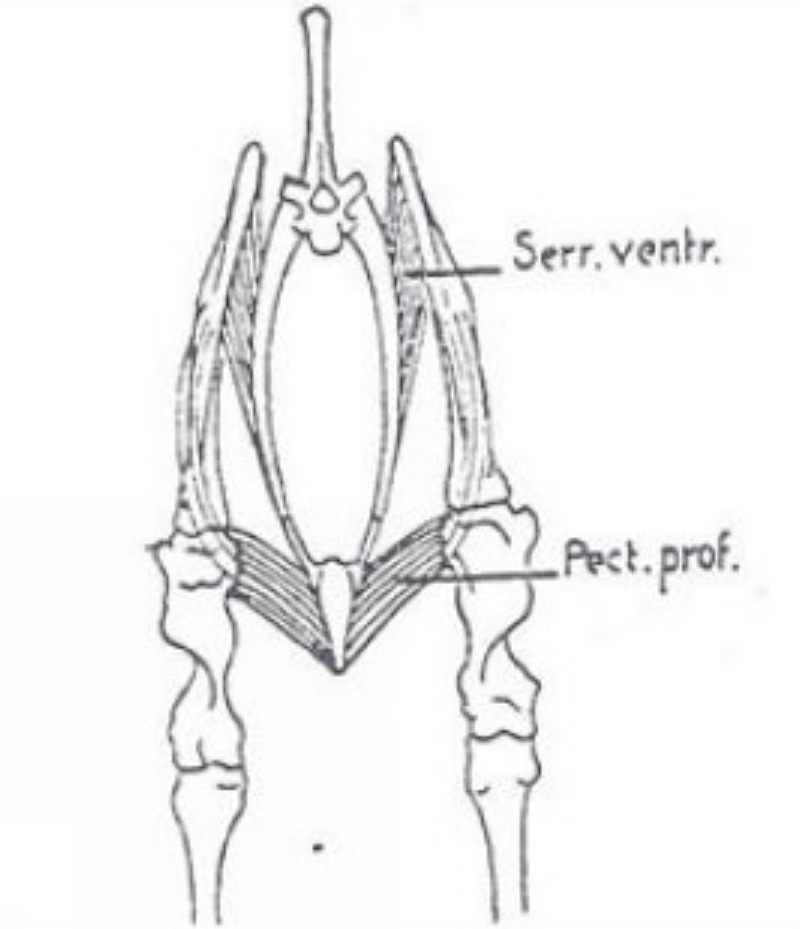

• Is part of the “Thoracic Sling” which suspends the horses chest cavity from the forelimb.

The forelimb of the horse is very different from the human and not just because the foot is encapsulated by a hoof! The horse doesn’t have a collar bone like humans, but instead relies on muscle known as a synsarcosis to hold the thorax and forelimbs together. This muscular ‘joint’ affects the kinetic chains and fascia of the entire horse. A dysfunction in this area can be highly detrimental to the whole body.

Contraction of the thoracic sling muscles lift the trunk and withers between the shoulder blades, raising the withers to the same height or higher than the croup (hind end). By contrast, a horse that is travelling without proper contraction of its sling muscles, or with weak sling muscles will appear downhill and be ‘on the forehand.’

The large serratus ventralis thoracis as well as its cervical elements are well adapted for the task of carrying the trunk between the forelegs and their job extends to more than moving and connecting the front legs to the thorax, but even to the action of the horse’s spine.

• Thought to contribute to the elastic properties of the forelimb.

. As part of the thoracic sling, it is a part of the process in which, as the neck lowers a little (within the normal range of movement and not with overbend), so the serratus ventralis comes into play, supporting the thorax and enabling the back to raise (as described in the dressage term ‘engagement’).

It is a vital muscle in both the extension of the front leg and the movement of the back when being ridden or engaged in athletic movement.

Main causes of problems in this muscle:

Injury/strain through poor tack, lameness, direct trauma (falling onto shoulder) and discipline, however it can also be affected by hoof growth or poor foot care..

For example:

• Discipline:

Jumping disciplines could predispose injury to the SVT due to the large concussive forces of landing that will increase the demand on the SVTs role in supporting and suspending the trunk from the forelimbs.

Tack:

Ill fitting saddles that restrict shoulder movement, (i.e too tight) can prevent the scapula (shoulder blade) from moving back through direct restriction and/or pain which could result in SVT weakening.

Over girthing or poor girth quality can directly impair the SVT through pinching and direct pressure that ultimately results in pain, injury and tension.

• Lameness:

Chronic offloading of one forelimb to the other unilaterally increases the demand of the SVT in suspending the trunk thus, exposing it to abnormal strain.

What might you see in your horse to suggest a possible problem with the SVT

As well as the way the horse is travelling (ie downhill )there may be other signs that your horse is tight, sore or weak in the Thoracic Sling muscles.

• Reduced forelimb stride length.

. Reduced shoulder extension & flexion.

. Poor respiration (Due to location of the SVT over the ribs tension & pain could hinder ribcage expansion).

. Poor turning particularly on the forehand.

. Refusal to jump.

. ‘grumpy’ to be tacked up / sensitive to the girth

. breathing problems; even appearing to hold their breath in canter or gallop so dropping out of that gait

. reluctance to have front feet picked out / stretched forward for the farrier

. difficulty going up or down hills

. reluctance to pick up a lead or tend to swap leads or cross-canter

.difficulty with banks, drops and other jumps or obstacles that require extra “reach” in front

. showing reluctance when asked for lengthened strides

. tiring more quickly during exercise, because of having to work against the tightness to go forward

So what to do next –

If you suspect a problem in your horse’s SVT you might talk first with an equine vet together with an equine bodyworker. It would be important to rule out any nerve damage and to check both sides of your horse for muscle damage. (Horses can sometimes throw a little extra weight across if both front legs are sore so that it becomes difficult to see which shoulder is the origin of a problem).

You can quite easily feel the superficial pectorals and serratus ventalis thoracics yourself to see if you think your horse may be tight here:

Gently run your hands over the surface of the skin and see how they feel. It is good to go over your whole horse so you have the possibility of comparing different areas of muscles. Are they:

* Tight

* Loose

* Consistent and smooth

* Bumpy and stringy

* Are there even holes or dents in the muscles

* Is your horse sensitive in the chest or girth area

If you think your horse may be sensitive or tight in this area, or lacking strength and muscle tone, Equine bodywork or physiotherapy. is a great way to detect and treat problem areas helping to free up your horse, make them more comfortable and therefore more able to work correctly and become strong.

This isn’t a common area of unjustly although it can often be insufficiently built for the job a horse is expected to undertake and tack can adversely affect its development. Driving horses also risk both injury and underdevelopment of this muscle and it is a muscle known to be prone to injury if tired or over worked.

Physiotherapy will look at both electro therapy modalities; laser, pulsed magnetic field therapy and ultrasound alongside massage and remedial exercises such as slow walking, weight shifting, balance work, long lining and slow pole work. A physiotherapist or hydrotherapist may also recommend work on an underwater treadmill at a slow walk and with the support of the water.

Prevention is always better than cure and there are a number of things you can do and look at to give your horse the best possible chance to have strong muscles for a lasting career and healthy life.

The stronger and healthier the muscle is the less likely it is to become injured. Correctly warming up and cooling down the muscle will also reduce injury risk, and this can be a simple addition to a horse’s training plan with a good amount of walking in hand or on long lines as a part of daily training and especially when coming back into work after a testing period. Having your horse’s saddle checked is of course vital but don’t forget their girth which can affect and injure the muscles if ill fitting or the wrong shape for your horse. With a greater research and understanding in this area has come the invention of a range of ergonomic girth’s and your equipment specialist or saddle fitter together with your equine bodyworker should be able to help you decide on the most appropriate girth for your horse and their discipline.

An important aspect of fitness training is ‘cross-training’ – so as not to only concentrate on developing the key muscles used for your particular sport, but also in developing the stability muscles required for postural strength. Many concepts in developing these postural muscles are drawn from both yoga and Pilates and can be applied across to the horse (even though he has four legs and not two)! Both yoga do Pilates recognise the need for cantering or developing a strong core. This together with body awareness or proprioception are two of the base areas of development for fitness and training for any discipline. Research in human athletes has shown that strengthening these muscles enhances athletic performance and reduces the incidence of injury. It has also been shown to be a very effective exercise program in accelerating the post-injury rehabilitation process in humans. In the horse the trainer needs exercises which aim to improve ‘core stability,’ ‘flexibility’ and ‘coordination.’

The presence of incorrect movement techniques can result in the inability to undertake a movement with maximum efficiency or with the least expenditure of energy.

A thoracic sling lift reaction can be used in a healthy horse who is happy to take part in it;

apply steady but gentle pressure with your finger starting at the sternum, sliding back over the pectoral muscles to an area to behind the girth. The horse will respond by lifting through the withers. This will activate the thoracic sling and the abdominal muscles. The lift should be held for about 5 seconds, then released. This stretch can be repeated 3 to 5 times as part of a stretching routine which might also include carrot stretches between the front legs and upwards with the head raised. As with most yoga or Pilates exercises, carrot stretches have the greatest effect when done as slowly as possible and held in place for as long as possible – about 5-10 seconds. Exercises for horses to strengthen the core stabilizing muscles can not only be used as part of a regular training program to enhance performance and reduce injury, but may also help to prevent the recurrence of back pain or problems with other muscle groups such as the thoracic sling in some horses who have suffered weakened or injuries in these areas.

For basic equine bodywork and full physiotherapy courses contact me through my website http://www.fyrafotter.se