Maintaining the correct function of the system and the development of muscle enables you to ride your horse without doing any damage. Horses work in a horizontal balance from poll to tail in spinal alignment, which is effectively two slings with a hanging basket in the middle supported by four pillars.

THERE ARE FOUR PARTS TO THIS

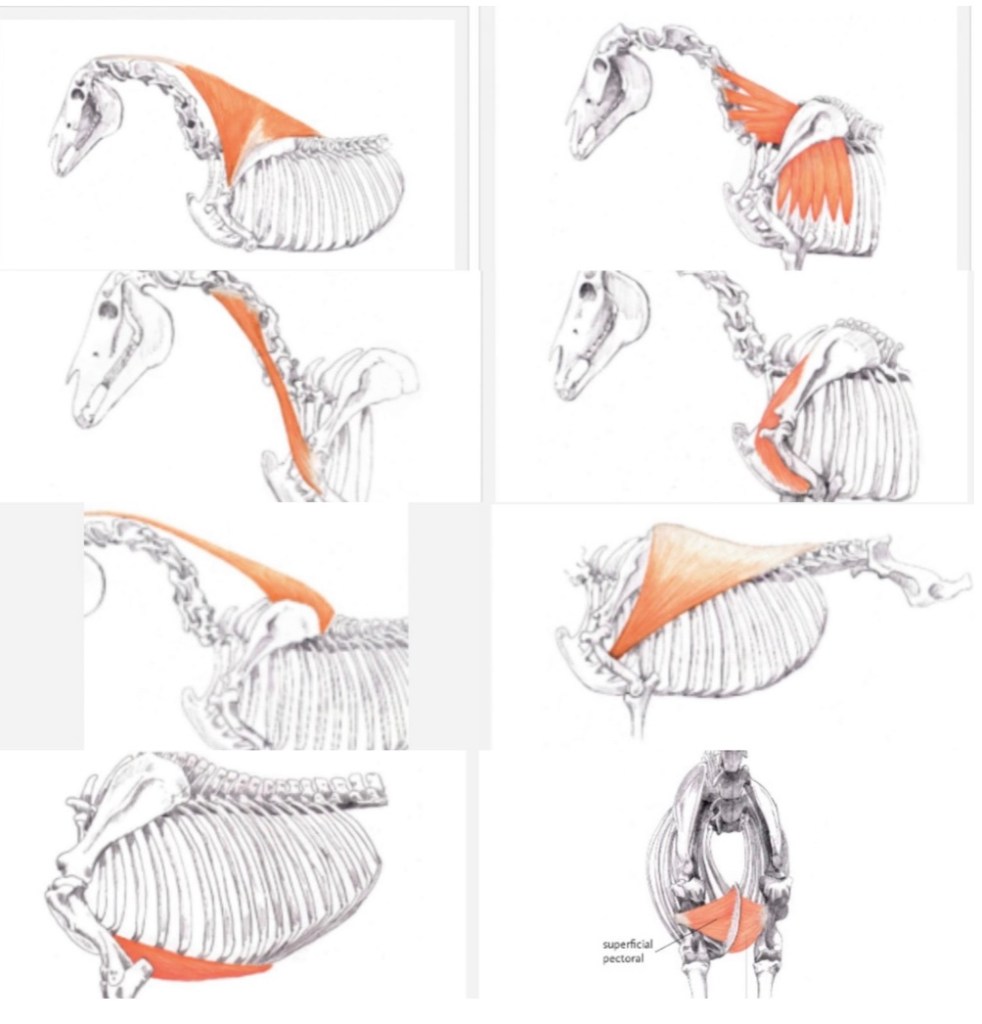

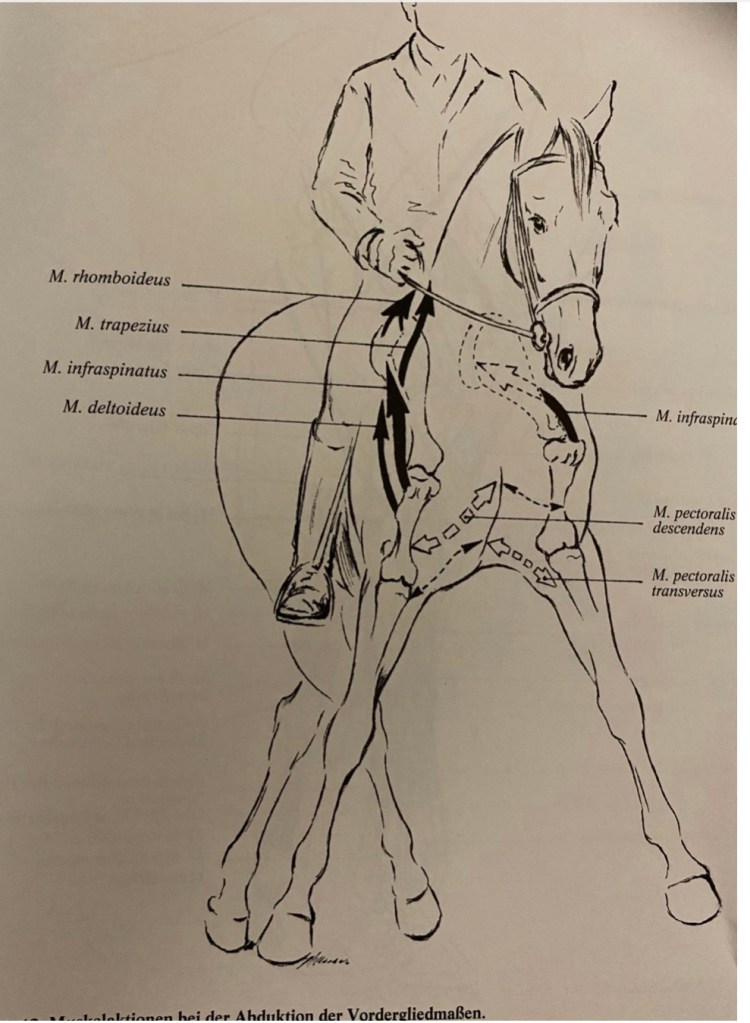

- the thoracic sling which is characterised by the shoulder, wither and neck in the front,

- the pelvic girdle which is in the back where our horse’s engine sits,

- the basket where the organs and ribcage are in between the suspension bridge and

- the legs which are the four pillars.

The importance of the thoracic sling is paramount and often misunderstood.

If we want to access our horse’s engine from behind we need to be able to open the throttle in the front, meaning the wither is lifted and supported by the upper neck muscles as well as engaging the muscles inside the horse.

These show up as a solid neck, and no dip in front of the wither or hollow behind the wither.

The horse needs to be able to lift the back and engage its core with its head at the poll being the highest point.

horse movement: structure, function and rehabilitation by Gail Williams.

In practice, I regularly see horses that are not moving forward freely and are leaning on the bit, they have compromised or weak thoracic sling muscles.

The sensation for the rider is of being slightly tipped forward with pressure on the toes to the stirrup. It can feel a bit locked or braced and it is hard to maintain a flowing movement with the horse. with this kind of movement comes a fear of losing control, and breathing (for both horse and rider) is a little compromised.

In this scenario, there is no room for the hind legs to come forward as the roadblock is in the front, and it is damaging for the horse’s lower neck, shoulder and elbow to travel like this.

To compensate the horse often has its hind legs behind the body which in turn overstretches the stifle and hocks, and you can often see them twisting a hindleg when they turn.

Most riders are instructed then to focus on engaging the hind end and moving forward, but if the thoracic sling is weak, the back can’t lift and carry the rider’s weight, and the back end has nothing to push except drive energy into the ground. (Think 4×4 with flat front tyres).

Another consequence of this is that they also place the hind legs in a wider stance past the body to give them stability, but again this compromises the hips, stifle and hocks and makes the back drop with the ribcage hanging on the shoulders.

When you look at horses from the side who are moving like this, their chest has slightly dropped and is in front and they end up with very weak muscles in the chest (bulging but soft) and if you look at them from the front the chest looks narrow and the front legs look closer together on the top, wider at the base.

There are metabolic effects to this way of moving and horses/ponies begin to appear to drop weight, showing their ribs despite a large grass belly and can develop a poorer coat with tougher areas around the ribs and flanks. The temptation by the riders is to feed a ‘topline’ feed product in an attempt to reclaim ‘condition,’ however it is not truly weight that has dropped but rather muscle that has gone.

Often we turn to pole work and this can help but only if they are in good posture, otherwise you are potentially exacerbating compensation patterns.

Most riders know that horses lack a clavicle or collar bone as it is commonly known.

The shoulders of a horse are attached by soft tissue; the horses body is slung in a soft tissue sling. This means the horse can swivel his chest in the sling, and rest on the sling.

As a therapist I will always check on the health of the sling. I will use myofascial release to help the sling reduce tension so it can do its job of shock absorption. If the sling is jammed down the horse will be relying on only its joints and hooves to absorb impact from the ground. As the horse is front heavy, a horse not using his sling will suffer more concussion which creates further problems. The goal of riding should be to have as healthy a sling as possible and have the horse use his sling as much as possible.

Riders may often focus on the hind end pushing through and ‘over the back’ or more often the position of the head. Learning to feel when the sling is engaged could prove more useful and help the horse carry you whilst strengthening the necessary muscles. Horses default to the easiest method to move. However this is proven to not be the most healthy for long term riding. Good riders actually train the thoracic sling all the time. Average riders will gain many benefits for their horses by concentrating more on the horses sling and shoulders and feeling when it is in use and thus strengthening.

During ridden work, for example when riding a circle, much is made of correct bend. The inside eyelash just visible, the horse following the arc of the circle, the contact of outside rein.

All true.

If the horse is performing the circle well, or a shoulder in or other exercise, the horse will swell underneath you.

This is the thoracic sling working properly

If a horse pushes his shoulder to the outside and sharply bends his neck to the inside (like a trailer jack-knifing), he is leaning on his thoracic sling (to the outside) and the swell is lost.

In other words he finds this more comfortable because he’s just hanging in the hammock of the sling.

When the sling is central, the horse cannot help but use it

When this happens, you will feel the swell. You are now strengthening your horse! You will know that the horse is using himself well.

It’s essential to be aware of this fact as the horse will cheat when he can and the gymnastic aim of the exercise is lost.

Some horses have a very ‘blocked’ sling.

Their withers are down and their chest is down and they hang out in their sling.

The horse on the forehand is hanging in his sling. To see proof of this while standing at your horses head ask your horse with a touch on his chest to rock back. The sling shifts back. You can touch the horse on the side of his chest and he will shift to the opposite way. He does this in riding. All good and correct riding keeps the sling in the middle so that the subscapularis and serratus muscles can lift and engage the sling into a bouncing, floating shock absorber which generates freedom and lightness in front.

If you are really lucky, you will start with a horse who does that naturally but any fit (unsick) horse can learn gradually to engage their core and use the sling rather than hanging in it.

To move forward you need to create lift, but to get lift you need to slow it down.

I like to compare this to a small child learning how to walk, as before you know it they are running, then they topple over, then they get their balance and then they slow down.

This is what we see with our horses too.

If we want to access our horse’s engine from behind we need to be able to open the throttle in the front, meaning the wither is lifted and supported by the upper neck muscles as well as engaging the muscles inside the horse.

Here are two exercises you can try to engage your horse’s thoracic sling without riding!

Exercise: Nose Forward Reach

WHAT

Also considered an incentive stretch, this exercise emphasizes core engagement by asking your horse to shift his weight forward toward a treat, without moving his feet.

WHY

– Activates the thoracic sling including the serratus ventralis, pectorals, and subclavius as well as hip/pelvis stabilizers including the gluteals, sacrocaudalis dorsalis, tensor fasciae latae, quadriceps, bicep femoris, adductors, and sartorius.

– Stretches the rectus capitis dorsalis and lateralis, multifidus cervicis, rhomboids, splenius, and trapezius.

– Increases balance and stability.

– Improves self-carriage.

HOW

1. Stand in front of your horse and hold one hand gently against his chest to stop any forward steps.

2. Offer a treat right in front of his nose to get his attention.

3. Slowly move the treat in a straight line away from the horse, enticing him to shift his weight forward toward the treat without taking a step.

4. When using a clicker, activate it 3–4 feet in front of the horse’s nose.

5. Make sure your horse’s neck is straight with no tilt and the nose is pointing forward toward the incentive.

6. Hold for 10 seconds to start, working up to 30 seconds over the course of several weeks.

7. Repeat 2–4 times.

WHEN

Every day, before or after work. Hold for 10–30 seconds and repeat 2–4 times.

Tips and Common Issues and Precautions

– The goal is for your horse to shift his weight forward without actually stepping forward, but watch your feet. Your horse will most likely take a few steps before you figure out how far you can move the incentive away or how much pressure you need to keep on the chest.

– Use a treat that you can wrap your hand around so the horse can smell but not eat it immediately, and will hold his forward stretch.

– Allow your horse to be in control of the stretch—do not pull him into position or hold his nose down.

Exercise: Weight Shift Back

WHAT

Ask your horse to shift his weight and/or rock backward without stepping back.

WHY

– Contracts the thoracic sling, multifidus, and muscles surrounding the stifle.

– Teaches your horse to load and engage the hind end.

HOW

1. Apply gentle pressure to your horse’s lead rope or chest, asking him to shift his weight backward without moving his feet.

2. Release pressure quickly so your horse doesn’t step back. The quick release is essential to keep your horse from actually stepping back.

WHEN

Every day, before or after work. Repeat 2–4 times.

Tips and Common Issues and Precautions

– If your horse refuses to shift his weight, try lifting and holding a front leg for 10 seconds to release some of the weight on the forehand before replacing the foot and trying the exercise again.

– Placing stability pads under the front legs can also help release weight and tension in the front, activating the stabilizer muscles so they are easier to recruit. Try placing a pad under one or both front feet for 15–20 seconds before removing them and trying the exercise again.

– For increased difficulty, lift one of your horse’s front legs and hold it up while asking for the weight shift.

There are a number of wonderful groundwork and long lining books available to teach you to train your horse from the ground (especially useful if you are not an advanced rider or if your horse’s muscle development does not yet allow him to engage his muscles correctly to carry a rider.

The above exercises are in several books but I took the descriptions from the wonderfully clear ‘Pilates for horses’ by Laura Reiman