Sacroiliac disease is debilitating and performance-limiting.

A lack of understanding about this condition can lead to inefficient treatment and even welfare problems for the horse—especially if handlers consider his issues to be behavior-related.

Know how to recognize the signs and work with your veterinarian and physiotherapist to get a diagnosis and personalized treatment program to help your horse get back on track and performing his best.

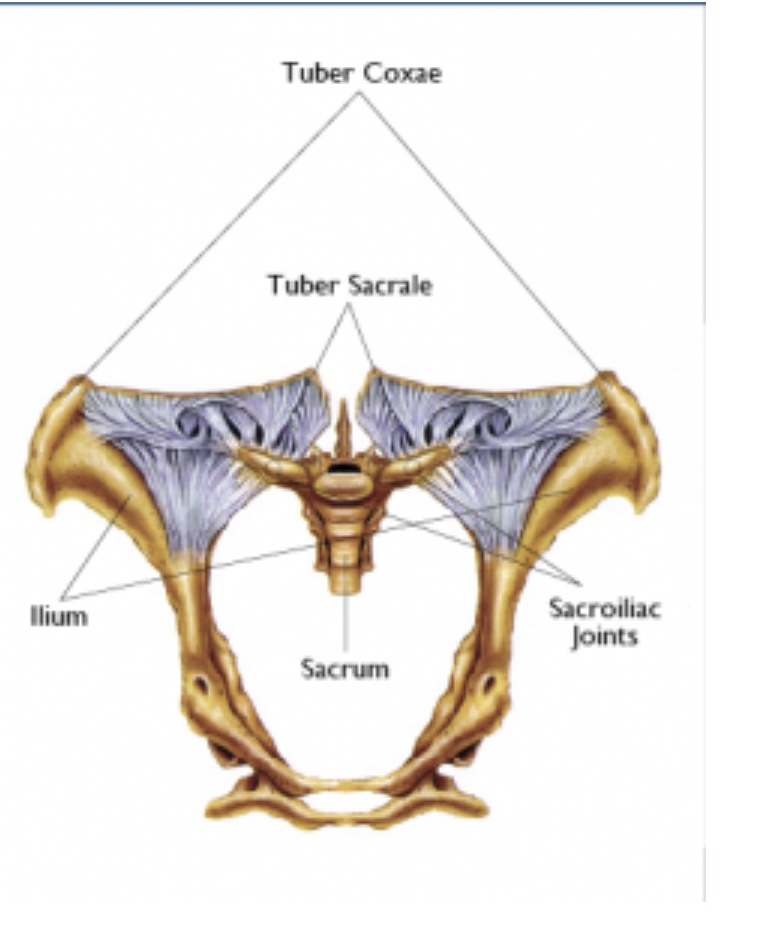

The sacroiliac (SI) region is the part of the horse’s back where, just as it sounds, the sacrum and the ilium unite. The ilium is the largest, fan-shaped bone of the pelvis, and the sacrum, which is also considered part of the pelvis, is made up of five fused vertebrae that form one solid unit just before the tail.

Two SI joints connect these bony structures, and a series of ligaments along the central aspect of the joints hold those joints together

The horse is able to move forward efficiently because of this SI region, which transfers forces from the horse’s hind legs to his back. Unlike most other joints and ligaments in the horse’s body, the SI region is designed more for stability and shock absorption than movement.

A horse gallops, jumps, collects, turns and extends his stride with power from his hindquarters. And his sacroiliac (SI) joint is critical at every stride. It transfers the action of his hind legs to his back, translating the push into forward motion.

Given the forces that this joint handles day in and day out, it’s not unusual for horses to develop SI pain. The trick is recognizing the problem: SI injuries are notoriously hard to pin down, with subtle and confusing signs, easily mistaken for other physical or even behavioral problems. Any horse can injure his SI joint in a fall or some other accident. The injury may leave the joint less stable than it was originally, so it can become a source of chronic pain. Performance horses may develop SI problems through simple wear and tear and the more mechanical stress the joint comes under, the greater the risk.

Ligaments can be torn, stretched, or otherwise damaged, and the bones can show arthritic changes. In most cases, it’s initially ligament damage that wasn’t originally recognized. However, when the damage has been there for a long time, it creates arthritis in the joints because they’re not properly supported by the ligaments anymore.

SI problems are fairly common. In one recent survey, these problems accounted for more than half of 124 horses presented for back problems at the University of Minnesota equine clinic. Sacroiliac disease is a relatively new field of scientific study, having only been described in literature since 2003. Researchers’ progress is leading to better recognition, diagnosis, prevention, treatment, and general understanding of this musculoskeletal issue.

Show jumping and dressage seem to be especially hard on the joint, according to a study carried out by Sue Dyson, FRCVS, and others at the Center for Equine Studies, Animal Health Trust, Newmarket, United Kingdom. That study analyzed records of 74 horses seen for SI pain at the center. Dressage horses and show jumpers accounted for almost 60 percent of the group. Slightly more than half were warmbloods, suggesting that breed may play a role. And horses with SI pain tended to be taller and heavier than average, another sign that mechanical stress is an important factor.

Under stress, the joint can be injured in several ways. The SI ligaments can tear, just as ligaments and tendons in a limb can give way under stress. And the joint itself, like the hock or any other joint, can become inflamed. Over time, osteoarthritis develops cartilage wears away and bone remodels. Thoroughbred racehorses sometimes get pelvic stress fractures directly over the SI joint, and those need to be differentiated from SI joint arthritis.

SI problems are hard to spot. The joint has almost no range of motion and is buried under layers of muscle and fat, so you can’t really see or feel it. And signs of SI pain are often frustratingly vague. Your first hint of trouble may be a change in your horse’s performance or attitude—he’s not working at his usual level or seems unwilling to work. He lacks impulsion behind, and his quality of movement isn’t what it was. Your farrier may tell you that your horse is difficult to shoe behind.

You may see other signs as well. Some may show up when your horse works on a longe line or in-hand. But often signs are worse when your horse is ridden or is asked to canter, because these demands call for more hind-limb impulsion and put more stress on the SI. Sometimes the signs are apparent only when your horse is ridden, and sometimes they are felt only from the saddle. Horses with SI problems may not look lame, even to a skilled observer, but they often feel worse to a rider.

Besides lack of impulsion and reduced quality of movement, you may notice that your horse

• is reluctant to move forward.

• bunny-hopping and

• lack of hindquarter coordination

• weight-shifting

• difficulty lifting the hind feet for hoof care

• holds his back rigid.

• tends to throw his rider upward and forward.

• is reluctant to work on the bit.

• has trouble with lateral work, such as shoulder-in and half-pass.

• is stiff and crooked at the canter.

• changes his leading hind leg (swaps off behind) at the canter.

• has trouble with flying lead changes.

• bucks and kicks out.

• refuses jumps.

• Working your horse in-hand (on a firm surface), you may also see that he travels with a wide-based gait behind and has trouble with foot placement on circles.

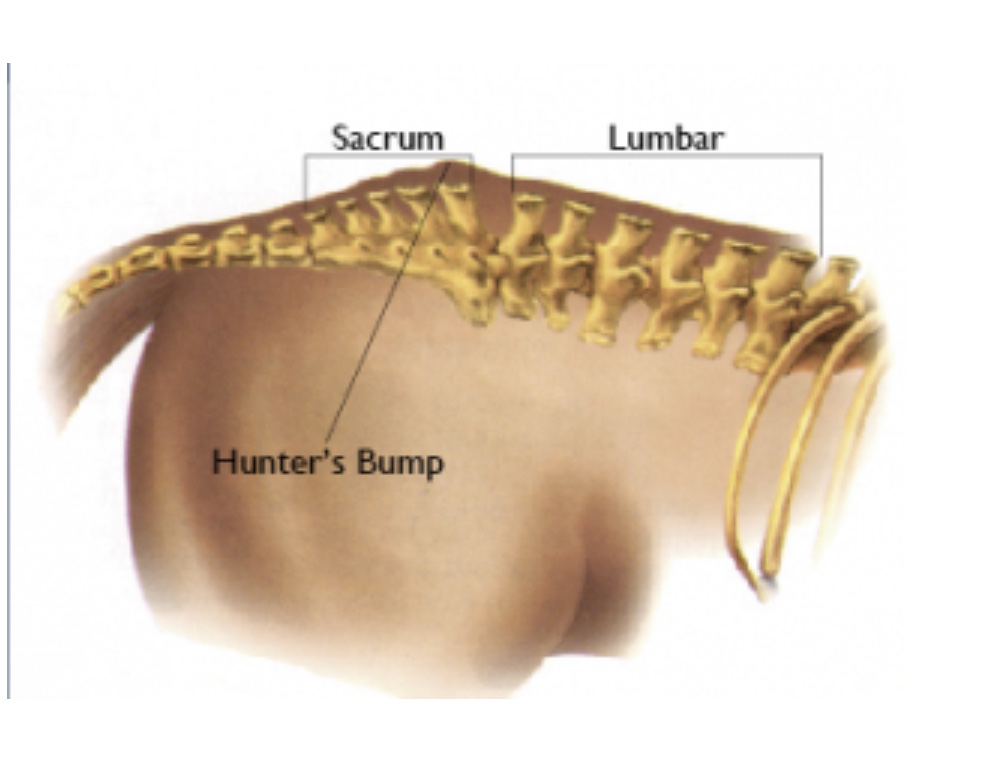

• A “hunter’s bump” just indicates a prominent bony crest (the tuber sacrale) underneath the muscles at the top of the croup.

• Prominence on one or both sides may be normal for a particular horse, but if your horse has pain, muscle spasms and joint stiffness in the SI or pelvic region, then the bump is likely to be significant. It may signal subluxation (a partial displacement of the tuber sacrale).

Asymmetrical muscling in the hindquarters is another red flag or, perhaps, a red herring. Unfortunately, most signs of SI pain can be produced by other conditions.

SI pain often appears along with other musculoskeletal problems.

Sacroiliac disease can appear in any age horse, and it’s often the compounding result of injury plus wear.

A particularly common concurrent injury is to the top of the hind suspensory ligaments that run down the back of each cannon bone, says Sue Dyson, MA, VetMB, PhD, DEO, FRCVS, head of Clinical Orthopaedics at the Animal Health Trust Centre for Equine Studies, in Newmarket, England.

“Frequently, the way they alter their movement because of the pain in their hind limbs places abnormal stress on the SI joints, and so they get secondary SI joint pain,” she says.

In Dr. Dyson’s study, 25 percent of the horses also had lameness in a front or hind limb, and another 25 percent had arthritis or other problems somewhere in their spines.

The problems are often related, but it can be hard to know what came first. How we train can contribute to SI disease onset, as well, says Dyson. And the shift in training styles over the years seems to be making the condition more common than it was 30 years ago. “Horses are being worked in a different way today,” she says.

Many more horses are being used for single disciplines. Many are working in arenas and not in a variety of situations. These contribute to wear and tear on the body. A horse that is asked to go in circles as a major part of his work is not doing what evolution has designed his body to do ie wander over vast plains and run away relatively fast, in a straight line, from predators.

Did a lower-leg lameness cause the horse to change his way of going in a way that stressed his SI? Or did SI pain cause him to alter his gaits in a way that overloaded a limb and caused the lameness?

Your horse’s performance history and a clinical examination are the starting points for the diagnosis. f the disease is affecting the joints, which can produce constant, moderate pain levels. They might also frequently shift their weight in the stall. These horses are also likely to be difficult to stand for the farrier and the first point of diagnosis may come as a referral from a sympathetic farrier to the vet or physiotherapist.

Your veterinarian and equine bodyworker will watch your horse in motion and perform a hands-on exam, checking for asymmetries and for pain in response to manual pressure. Only the top parts of the dorsal (upper) SI ligaments can be felt directly, and signs of pain and swelling here suggest ligament damage. The joint itself and the ventral ligaments are too deep to check this way, but rectal palpation of the SI region by a skilled osteopathic veterinarian may also produce a pain response.

Sacroiliac disease is easy to mistake for other problems. Owners and veterinarians often think they’re seeing conditions such as ataxia, hock arthritis, or stifle arthritis first and SI disease is only looked into later in a process of the disease.

The SI joint can also be blocked with an injection of local anesthesia (in the same way that nerve or joint blocks are done in the limbs). This test can confirm that the SI region is the source of your horse’s discomfort, but it doesn’t tell exactly what’s going on.

The joint’s deep location makes it difficult to image, but several techniques can help zero in on the nature of the problem:

• A bone scan (nuclear scintigraphy) can reveal osteoarthritis. Your horse is injected with a radioactive substance that accumulates in areas of active bone remodeling, and a gamma camera tracks the substance as it moves through his body.

• Ultrasound scans can detect damage to ligaments. Transrectal ultrasound (the technique used for equine pregnancy checks) may reveal irregular SI joint margins—a sign of arthritis—as well as damage to the ventral (lower) SI ligament.

• Ultrasound or radiographs can help identify a displaced tuber sacrale.

• Scintigraphy and ultrasound might reveal changes in ligament fiber patterns or lesions in the attachments between ligament and bone, he says. Bones can be rough or even show signs of fragmentation or avulsion (when a piece of bone breaks off because of a tendon or ligament’s pull). Ligaments that have been damaged for a long time can become thickened, making them less flexible

• A ridden lameness exam is a must, says Dyson. “You have to see the horse perform ridden,” she says. “We see every horse ridden unless he’s too lame to be ridden.”

Even with these tools, it’s sometimes hard to figure out the exact nature of an SI problem. But knowing the cause of your horse’s pain will increase the odds of successful treatment and make a relapse less likely.

The good news is that sacroiliac disease is treatable, and conservative nonsurgical methods can be very effective. While prognosis is better if the disease is caught early, the chances of returning to previous athletic levels are generally quite high. 90% of horses treated for this condition usually return to their original level of work (or higher) if the problem is caught early.

Horses that have been performing poorly for a year or more could present greater treatment challenges

Physiotherapy offers a physical training program attuned to the individual horse, as the disease can affect different combinations of structures in different ways. A veterinarian can develop a program of targeted treatment in combination with physiotherapy, designed to bring relief and healing in the right order, with the right timing.

Treatment typically begins with stall rest and anti-inflammatories. And the veterinarian should first address any primary causes, such as a hind-limb injury. Veterinarians sometimes inject corticosteroids using a specific technique to reach the inflamed SI joint.

Medication, reduced exercise, physical therapy and alternative therapies may all play a role in the program. Here are three key components:

• Reduce inflammation. This is the first step in treating SI pain. Your veterinarian may prescribe a course of oral phenylbutazone (bute) or another nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. If arthritis or ligament damage is diagnosed, local injections of corticosteroids can help reduce pain and inflammation. The injections are similar to those used in other inflamed joints, such as the hock.

• Reduce exercise. Limited exercise helps by strengthening the muscles that surround the joint but too much work will aggravate the injury. Your veterinarian can help determine how much and what type of exercise is best for your horse. The program might call for light work in-hand, on the longe line or in a round pen for several weeks. If your horse is comfortable with that, you might start light riding at the walk and then at the trot. Increase work slowly, watching carefully for signs that your horse is uncomfortable or unwilling.

• Allow turnout. Stall rest isn’t recommended for most SI injuries. In most cases, turnout in a small paddock with good footing is helpful. Avoid deep mud, large rocks, poor footing and steep hills, which may aggravate SI problems.

After proper diagnosis, real healing of the SI region begins with exercise. Using a nonridden … program, working with the horse as round as they can manage (e.g., in a Pessoa rig or equi-ami). The program encourages them to work over poles on the ground. When the horse is making satisfactory progress the physiotherapist will attempt to begin the horse under saddle again and get them working on things that the horse finds easy, avoiding lateral work and cantering initially, because the rotational movement of the pelvis causes pain.

Good basic gymnastic strengthening through dressage provides the basis for strengthening all disciplines. And this is especially true for horses battling SI issues because of their need for core strength and stability.

That core training is also critical to helping build the topline muscles, which SI-affected horses quickly lose when they try to minimize discomfort. They get into a downward cycle because if they’re not using the muscles, those muscles are wasting away, and then they don’t have the support for their SI area, so the horse loses the core stability.

Arthritis in the SI joint can lead to chronic, low-grade pain. In this case, careful management will help keep your horse comfortable.

• Use a progressive (gradually increasing) exercise program to strengthen and supple his hindquarters. Tailor the length, frequency and intensity of the work to suit your horse, Dr. Haussler says, backing off if your horse seems unwilling or if other trouble signs return.

• Use cross-training techniques for example, alternate flatwork, hacks in the field and cavalletti work to avoid constant or repetitive stress on the joint.

• Avoid activities that are especially hard on the SI region: jumping, galloping, abrupt transitions, tight turns and circles.

• Turn out your horse as much as possible. Moving around at liberty will help him maintain flexibility, reducing joint stiffness.

Several alternative therapies may help keep your horse on the road to recovery:

• Acupuncture may be useful for pain control in the SI region.

• Therapeutic exercises can help restore impulsion and coordination in the hind limbs. Hind-limb stretching exercises that draw the leg forward (protraction) and backward (retraction) may help relax spastic muscles or contracted connective tissue and restore joint mobility.

• Laser, ultrasound and pulsed electromagnetic therapy can offer pain relief, reduction in inflammation and help in healing

• Chiropractic or osteopathic techniques may be helpful in chronic cases to restore normal, pain-free joint mobility.

• Massage may help relax muscle tightness in the croup or upper hind limbs.

The outlook for horses with SI injuries depends on the severity and duration of the problem. A horse with a mild injury should recover and has a good chance of returning to full work. Horses with more severe cases of osteoarthritis or ligament damage may return to a low level of exercise, but their outlook for returning to high performance isn’t so good.

As a rule, a horse who responds well to treatment has a better chance of full recovery than one who does not.

Sacroiliac disease is debilitating and performance-limiting. A lack of understanding about this condition can lead to inefficient treatment and even welfare problems for the horse, especially if his handler only sees the behaviour problems and is unaware of the underlying pain that accompanies those difficulties.