While forelimb lamenesses are fairly common, hind-limb issues can be less obvious and even underdiagnosed. Learn about the common causes of lameness in the back legs and hind quarters.

One of the signs of any lameness or discomfort in the movement of a horse is a seemingly unlevel movement- the nod of a head or a sound difference in hoofs as they land. What exactly does a hind-limb lameness look like? Front end lamenesses are often easier to detect as we can focus on the head in walk and trot. A head bob, or a dramatic raising of the head when the lame leg bears weight, is a telltale sign of forelimb lameness, as the horse tries to use the fulcrum of his head and neck to take the weight away from the sore limb

Excessive hip movement or “hip hikes,” an unwillingness to bring a leg forward, toe dragging, and a “bunny hopping” canter are just a few routine signs of hind-end lameness. No two horses show hind end problems in exactly the same way.

Before choosing an imaging method, veterinarians usually perform diagnostic analgesia (joint blocking) to isolate lameness to a certain area. Because vets perform most of their equine work on the farm, stallside radiographs (X rays) are the modality of choice for evaluating any bone or joint in this setting. Radiography, however, does not reveal many details about soft tissue. Ultrasound is ideal for evaluating tendons, ligaments, or other soft tissue structures in the field.

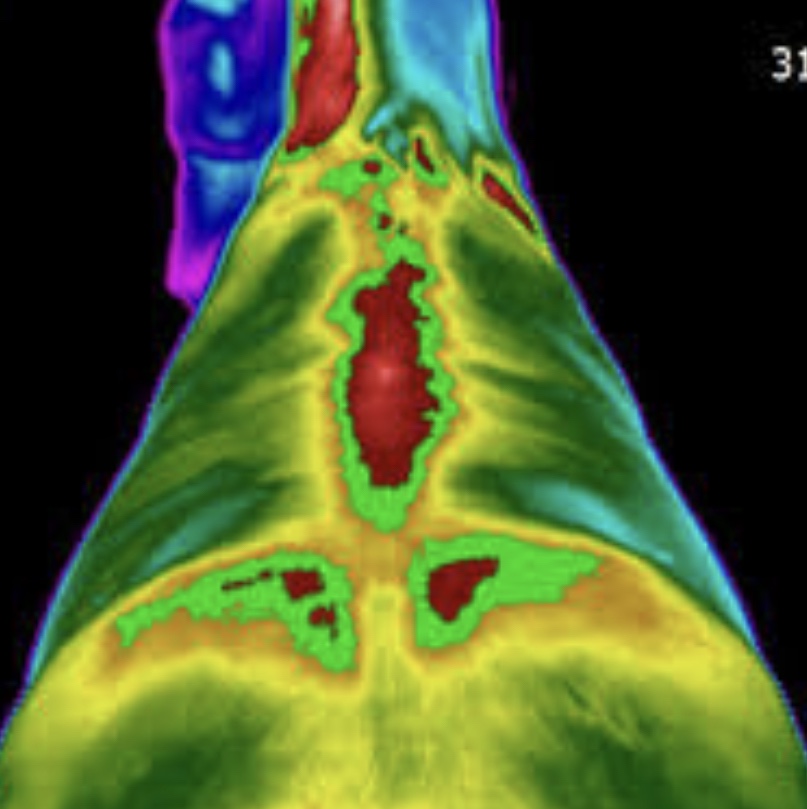

In veterinary Rehabilitation therapy I have used thermography and gait analysis to assist the veterinarian and pressure walkways as well as computer analysed sensors on the feet can also be used.

Thermography with a heat detecting camera is another means for checking lameness as is gait analysis with pressure pads or by taking a film and slowing it right down on gait analysis software.

More and more veterinarians are recognizing sacroiliac—the area where the spinal column meets the pelvis—pain (often described as SI pain) as a cause of hind-limb discomfort, particularly in performance horses. Common signs of pain in this region include a reluctance to go forward, lack of impulsion, and an uncoordinated “bunny hop” canter, among others.

The sacrum is a section of five fused vertebrae located between the lumbar spine and coccygeal (tail) segment. It is the ‘sacro’ part of the sacroiliac joint. Its widest point, known as the sacrum, connects to the underside of the pelvis, known as the ilium (the ‘iliac’ part of the sacroiliac joint). This connection forms the sacroiliac joint.

Subluxation (misalignment) and osteoarthritis are the main causes of discomfort to the sacroiliac joint.This may be exacerbated by a more pressing source of pain, often pointing lower down the leg to problems in the hock or stifle (knee) of the horse.

Because the SI joint is beneath many centimetres of muscle, imaging the area can be challenging. X-rays are often not clear and nuclear scintigraphy (bone scans) may not be readily available so ultrasound combined with nerve blocks, experience and a knowledge of equine chiropractic/physiotherapy offers a way to consider problems in this area.

Treatment often involves chiropractic adjustments by the physiotherapist, chiropractor , osteopath or other competent bodyworker and corticosteroid injections by the veterinarian.

A further and relatively common back limb problem is the upward fixation of the patella in the knee known as a locking stifle. An injury well known in human sports medicine among football players, and in the canine physio world as especially common in some smaller breeds, this upward movement and the sense that the leg gets stuck is uncomfortable and a one imagines quite frightening to the horses whose ability to move away fast is a vital part of their survival mechanism.

Most commonly seen in young horses and ponies, it occurs when the medial patellar ligament (which connects the patella, in the stifle joint, to the tibia below) gets ‘stuck’ on the femur during limb extension. The signs can be quite variable in severity and frequency. The other end of the age spectrum is in older horses who have lost muscle in the quadriceps area. The fact that this affects young and old but not commonly fit and mature horses points to one of the ways to resolve this by strengthening certain muscles. By working to strengthen the quadriceps muscle and often by using kinesiology tape to guide the leg, the physiotherapist is often the main source of rehabilitation in cases of patella subluxation. In cases of complete fixation, the stifle and hock become locked in extension, and the horse might hop and drag his toe behind him to move. When the ligament releases, it appears as a jerking movement. Some veterinarians will advise surgical intervention for patella subluxation.

The cause of upward fixation of the patella is not well-understood, although researchers have identified some predisposing factors. These might include:

- Straight hind-limb conformation;

- Upright medial (inner) hoof walls and elongated toes;

- Weak quadriceps (a group of muscles that controls the stifle’s position and serves to extend the joint) and poor muscling in young horses;

- Prolonged periods of stall rest or time off from work due to other injuries;

- Breed, due to a hereditary component (Shetlands, specifically, are affected).

In the veterinarian’s initial examination, they should evaluate the horse’s gait and radiograph (X ray) and potentially ultrasound the stifle(s) to ensure the horse doesn’t have concurrent stifle disease, as this can change the course of treatment.

A conditioning program is key for young or weak horses with intermittent upward fixation. Conditioning should focus on strengthening the quadriceps. This is often done by incorporating hill work in which the horse is asked to walk up and down hills several times per day and given specific hill based exercises by the physiotherapist or bodyworker. Limiting time in the stall is also beneficial. Obviously a good foot trim and balanced hooves are essential in building the muscles of the legs.

If exercise is unsuccessful alone, then injections of iodine into the joint to irritate can be used to cause deliberate inflammation and consequent tightening of the ligament in healing. This is a treatment with very mixed results and likely quite some pain and discomfort to the horse in the process.

is unsuccessful or for moderate-to-severe or recurrent cases, the current surgical treatment of choice is medial patellar ligament desmoplasty (splitting). Surgeons complete this procedure with the horse either under brief general anesthesia or standing with local anesthesia. They use a blade or needle (sometimes guided by ultrasound) to make small incisions in the medial patellar ligament to cause it to tighten and become inflamed. The horse can go back to light work the following day. Exercise is important post-desmoplasty because the resulting inflammation helps tighten that ligament.

The overall success rate for this procedure varies, but researchers have reported it to be 70-90%. In cases that do not respond to medical management and splitting, or when the patella remains persistently locked, medial patella ligament desmoty (cutting the ligament completely to release the locked patella) is the surgical treatment often offered. Surgeons perform this under standing sedation.

Although this is a straightforward resolution to the problem, it is not without complications, including development of secondary osteoarthritis of the stifle. Therefore, desmotomy should only be performed when necessary. This procedure also requires that the horse have more time off from work which is contraindicated in a number of conditions that often come with the patella issue.

The most common hind end lamenesses occur due to soft tissue strains and tears. Ultrasound is often used to determine the area of soft tissue injury but thermography is now thought to offer considerable possibilities in soft tissue injury diagnosis. Treatment may involve laser, ultrasound or PEMF (pulsed electromagnetic field) therapies alongside acupuncture or cupping and massage. Cryotherapy (ice and heat alternating) may be used in the early stages.

Treatment also involves controlled exercise under the guidance of an equine exercise practitioner such as a physiotherapist or equine fitness instructor. The physiotherapist may use kinesiology taping to aid the recover program.

The major consideration in soft tissue injuries is that the return to work must be extremely slow and controlled to reduce the danger of permanent damage. Extracorporeal shock wave treatment is also a possibility for the recovery appears to have stopped or plateaued.