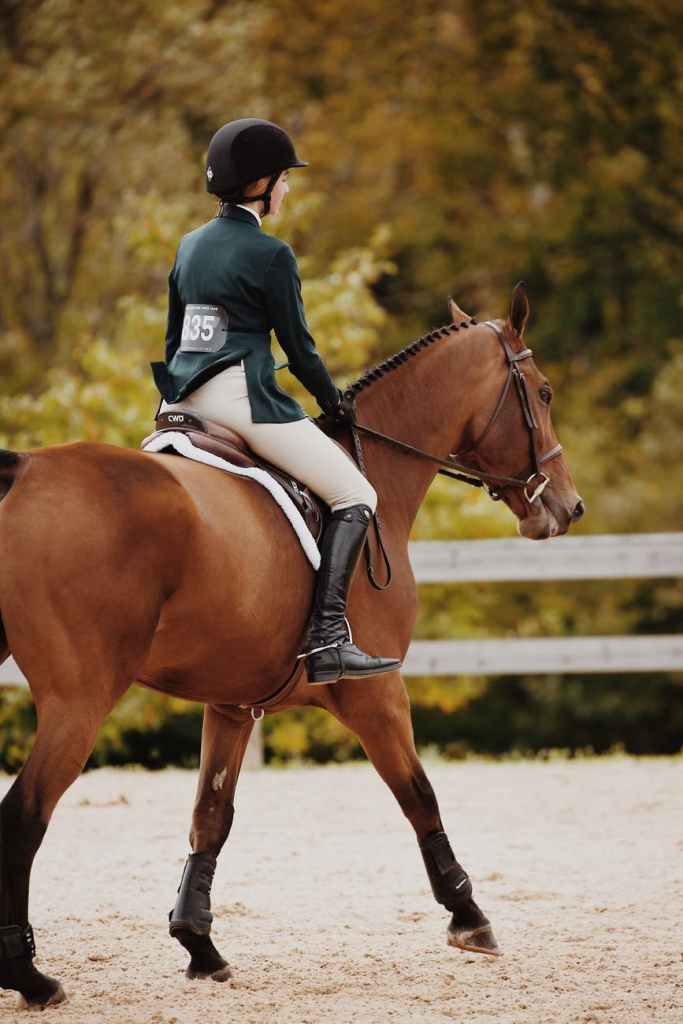

A brief information blog for equine bodyworkers!

What is PSSM?

- Polysaccharide storage myopathy (PSSM) is a disease that results in an abnormal accumulation of glycogen (sugar) in the muscles.

- Clinical signs may include reluctance to move, sweating, and muscle tremors, also known as “tying-up”.

- There are two types of PSSM. Type 1 is caused by a known genetic mutation and a DNA test is available. Type 2 may also be genetic, but the exact cause is unknown. There are currently no scientifically verified DNA tests for PSSM2, but a muscle biopsy can be performed for diagnosis.

- There is no cure for PSSM, but most affected horses can be managed successfully through diet and exercise.

Two types of PSSM have been identified, PSSM1 and PSSM2. A genetic mutation in the glycogen synthase 1 (GYS1) gene causes PSSM Type 1 (PSSM1). The mutation causes muscle cells to produce glycogen continually. Since it is an autosomal dominant trait, only one copy of the mutation is needed for a horse to be affected. However, environmental factors, namely diet and exercise, play important roles in the onset of clinical signs. PSSM1 is more commonly observed in Quarter Horses, related breeds such as Paints and Appaloosas, and draft breeds, although cases have been reported in more than 20 breeds.

Polysaccharide storage myopathy type 2 (PSSM2) also results in abnormal glycogen storage in muscle, but horses do not have the GYS1 mutation. The cause of PSSM2 remains unknown; there may actually be multiple causes. A condition known as myofibrillar myopathy (MFM), characterized by exercise intolerance and intermittent exertional rhabdomyolysis, may be an extreme subset of PSSM2, but further research is needed. PSSM2, but not MFM, has been diagnosed in Quarter horses. Cases of PSSM2/MFM have been reported in warmbloods and Arabians. My experiences of this were with my 3/4 Arab with 1/4 Welsh section D and only seen twice when he simply stopped and quite clearly (as a very enthusiastic equine partner) could not offer very much. In both cases it was during training for endurance competitions.

The most susceptible horse breeds are American paint, quarter horse, thoroughbred cobs, warmblood, dales, new forest, Morgan Peruvian, paso fino, mustang, Lipizzaner, standard breed, Arabian and draft (bruks). Some consider that draft horses are described as more prone to PSSM as they were often fed more carbohydrates for their work in the past.

He sweated and I saw muscle tremors in his leg muscles without enormous amounts of exercise. We managed it and he continued to ride and compete as well as to live into his 40s. I will discuss management later in the blog!

Generally the clinical signs of PSSM range from mild to severe. Horses present with muscular weakness, lethargy, reluctant to rise, muscle damage, increase serum creatinine, and reduced performance.

Owners often notice the disease in terms of sweating, lameness, sore muscles, undiagnosed lameness, poor performance, and muscle tremors (“tying up”). These may occur with or without exercise.

When ridden, affected horses may be reluctant to go forward or collect.

Some affected horses, however, do not exhibit any clinical signs. This is the danger from a breeding perspective!

While PSSM1 is diagnosed with a DNA test, the tests for version 2 are more complex as there are other basis for ‘tying up’ symptoms like muscle tremors and lameness!

A muscle biopsy may be taken to evaluate muscle damage and measure the amount of glycogen in the muscle.

There are other causes for tying-up besides PSSM, including malignant hypothermia, glycogen branching enzyme deficiency, literally working on a full stomach can give a similar effect and myosin heavy chain myopathy presents similar symptoms so it is important to rule these out to ensure the horse is treated appropriately.

The process of glucose storage in the body may be helpful to consider here, before we look at management methods. Diet is one of the major management methods!

Glucose is the end product of carbohydrate metabolism. The glucose is used for the production of energy within the cell by catabolism. The unused glucose stored in the liver cell and muscle cells as glycogen (a polymer of glucose). These stored glycogen are used for energy production (Glycolysis) during the additional requirement. Any disruption of the process leads to glycogen storage diseases or PSSM.

The diet should be composed of low sugar and starch, not more than 1.5 to 2% of the horse’s body weight per day. The total non-structural carbohydrate (NSC) should not be not more than 12% of the diet to keep insulin levels low and reduce glycogen storage in the muscles. The horse diet should have vitamins, minerals, protein, and fat in a balanced way, and you can add a muscle supplement to feed too.

It is important to minimize sugar and starch in the horse’s diet to prevent excessive accumulation of glycogen as dugars in the diet trigger insulin release from the pancreas, which stimulates glucose uptake into muscle and glycogen synthesis.

Horses with PSSM are highly insulin sensitive and have greater glucose uptake into muscle than other horses.

Providing a diet that is low in starch and sugar will limit the release of insulin and the stimulation of glycogen synthesis.

It is recommended that the total diet provide less than 12% of the energy from non-structural carbohydrates(NSC), though some authorities aim for less than 10%. The NSC value is calculated from the combination of ethanol-soluble carbohydrates (ESC) and starch. Affected horses are often easy keepers and management through a low-NSC grass hay and a good-quality ration balancer is usually sufficient. If additional calories are needed, a low-NSC and/or high fat feed source should be incorporated.

There are a few things to consider for lowering the NSC content of the total diet:

- Eliminate concentrate feeds:These often contain processed grains that are high in starch and sugars. Many complete feeds and commercial rations are high in NSC, and not all disclose the NSC content on the label. An equine nutritionalist can be a helpful addition to the ‘team around the horse,’ in this regard.

- Choose a low-NSC hay: If possible, choose a hay with an NSC value of 12% or less.

- Soak the hay: Soaking hay helps reduce the level of soluble carbohydrates. Aim for 30 minutes (with warm water) or 60 minutes (with cold water) and allow it to drain for 10 minutes afterwards. Obviously this can be very hard in places where winter results in icy conditions so a naturally low NSC fodder is the better option then.

- Use a slow feeder hay net: This helps extend the foraging time so that any sugars they are consuming enters the body over a longer period of time and results in lower insulin release.

- Use a grazing muzzle: If fresh, lush pasture cannot be avoided, consider using a grazing muzzle to limit their intake.

- Limit pasture access to the early morning: Another option for lowering sugar intake from pasture is to limit pasture access to the early morning hours when the plants naturally have lower sugar levels.

- Use a track system to support both movement and ’trickle feeding.’

Note that one should never try to lower the NSC content of a horse’s diet by underfeeding forages (grass, straw and hay). Not providing adequate forage can lead to other issues such as gastric ulcers, behavioural problems and hind gut dysfunction.

Always aim to feed 1.5 – 2% of the horse’s ideal weight (note the word ideal here) as forage. This is equivalent to 7– 9 kg (15 – 20 lbs) of hay per day for a 500 kg (1100 lb) horse

Horses with PSSM can (and should) work and exercise and even compete so what about the extra calorific needs of a working life? Fat offers a really good solution here!

Fat does not trigger insulin release and will not be stored as glycogen in muscle. Therefore, if your horse requires additional energy beyond what they are getting from their forage, fat is the preferred choice.

Horses with PSSM can have up to 20% of their caloric needs met by fat. This is best achieved with fat sources that are high in triglycerides which are easily digested and absorbed in the small intestine.

If the horse requires additional calories, a common recommendation is to add 0.5 kg (1 lb) of dietary fat for a 500 kg (1100 lb) horse. This can be accomplished by adding 2 cups of oil to their feed.

One of the important issues in diet is accurately scoring the condition of the horse. Once this is done, horses with a score of 4 or lower should have supplementary fat, while those who are at the ‘fat end of the spectrum’ need increased exercise.

Fat can in fact be a treatment method for PSSM horses. In a small study of 4 horses, exercise tolerance improved in horses fed diets providing 12% of calories from fat instead of 7%. This diet had lower starch content (3% compared to 21% of calories from starch). (Reported in J Vet Intern Med2004;18:887–894 ‘The Effect of Varying Dietary Starch and Fat Content on SerumCreatine Kinase Activity and Substrate Availability in EquinePolysaccharide Storage Myopathy’ was studied by W.P. Ribeiro, S.J. Valberg, J.D. Pagan, and B. Essen Gustavsson)

Low NSC fats appropriate for horses would include; omega3 rich oils like flax. Ground flax can be fed directly which is very oily, containing around 40% oil on average without making into or storing as an oil.

Rice bran can be fed as a source of fat. While it consists of approximately 20% fat, it also contains high levels of phosphorus, which needs to be appropriately balanced with calcium in the diet.

A special oil called w-3 oil offers DHA sourced from algae, which has shown to be very useful in the management of PSSM. It claims to offer the benefits of fish oils without the fish taste and smell which is off putting to many horses. Fish oils (salmon or cod liver) are also a good source of omega 3 and calories but not a normal source of food for the equine digestive tract.

Fat sources need to be introduced slowly to avoid digestive upset. For oils, start with 30 ml (1 oz) and increase it every 3-4 days to reach the desired amount over a 2-3 week period.

Feeding a low-NSC, high-fat diet can have additional benefits including reducing the risk of laminitis, colic and gastric ulcers.

These horses need an adequate source of selenium and vitamin E.

Selenium and vitamin E are important antioxidants that support healthy muscle function and recovery from exercise. PSSM horses with low vitamin E and selenium intake may be more prone to muscle cramping and stiffness.

Vitamin E and selenium work together, so if the horse is deficient in one of these nutrients, the other cannot function properly.

The American National Research Council Nutrient Requirements of Horses recommends a vitamin E intake of 500 – 1000 IU for a mature horse at maintenance.

To avoid selenium deficiency, the NRC recommends at least 1 mg selenium per day. The optimal intake is closer to 2 – 3 mg per day.

For horses prone to exertional rhabdomyolysis, it is recommended to provide 1500 – 2500 IU of vitamin E and 3 mg of selenium in the total diet.

Always choose organic/chelated sources of selenium and avoid over-feeding to prevent symptoms of selenium toxicity. The upper tolerable intake of selenium for a 500 kg (1100 lb) horse is 20 mg per day.

Ensure the horse has a good supply of amino acids appropriate to his or her needs.

Muscle atrophy is a common symptom of PSSM that can be partially mitigated by providing adequate levels of key amino acids in the diet.

For PSSM horses, the most appropriate strategy for providing adequate amino acid supply is to add protein or amino acid sources on their own, rather than as part of a complete feed. This helps minimize unwanted starch and sugars in the diet.

Other protein sources that provide a good balance of essential amino acids to support muscle growth and maintenance include:

- Alfalfa hay or cubes

- Soybean meal

- Canola meal

- Hempseed meal

- Flaxseed meal

- Whey protein

- Well balanced amino acid blends from a reputable feed company

The quantity of additional protein or amino acids that may be required will depend on the protein content of the hay offered to the horse. For horses in light to moderate exercise, the protein content of moderate-quality hay is typically sufficient to meet their needs.

If management of the diet eliminates the use of complete feeds and concentrates from the horse’s feeding plan to lower the overall NSC content, it may unintentionally create a nutrient deficiency in the horse’s diet.

Horses almost never obtain all of the vitamins and minerals they require from forage alone.

In addition to selenium and vitamin E, some of the vitamins and minerals that are important for supporting metabolic health and muscle function include:

- Zinc

- Copper

- Magnesium

- B-vitamins

It is recommended to provide a low-inclusion, comprehensive vitamin and mineral supplement to ensure the horse’s needs are met without oversupplying calories. Selecting a supplement that does not contain high-NSC fillers is a really important part of the dietary management so it is important to read the ingredients in any supplement used and to understand what information is or is not offered on feed and supplement packets.

Horses must exercise daily to maximize the muscles’ ability to burn glycogen. Stress is also reported to be a triggering factor for some horses so living outside in a stable herd can be a great solution for such horses.

Exercises include walking, lunging or long lining, riding and turnout.

Warming up before and cooling down after exercise becomes even more important. The exercise aims to help to burn the carbohydrate within the bloodstream, and less glucose will deposit to the muscle cells. As such it is important not to do too much heavy exercise without breaks to lower level exercises.

Resting should be more gentle movement and less stabling.

Complete rest and living in a stable and small paddock environment should be absolutely avoided.

These horses need movement (but then I would argue so do all horses)!

I would suggest that some stable vices, such as pacing round and around and weaving over doors may come from horses who need to keep moving to reduce the fear of ‘tying up’ from too much glycogen in the muscles. The more we limit their ability to do what we consider bad, the more aversive the environment becomes both to their body and then their sense of well-being.

Living in a larger group with more movement in larger older mixed grass and herb pastures or on tracks has been shown to promote greater movement and more overall fitness in horses generally so it is a good solution for horses with PSSM.

Since small management changes can have a big impact, fine-tuning the diet and exercise regimen over time may be necessary. Competition is not necessarily avoided and even for a high performance horse, PSSM can be managed through turn out, diet and exercise, stretching and appropriate time spent in warm up and chill down activities.

Medicines

In some cases, sedatives, analgesics, muscle relaxants, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be used to provide pain relief, especially for short periods after active episodes of tying up.

There is less evidence-based data available regarding management of horses with PSSM2 than those with PSSM1, but they are often treated similarly.

Equine therapists can also offer good solutions for acute bouts of tying up in the early stages through the use of muscle relaxing and activating tools (electrotherapies like ultrasound, laser, tens and PEMF) as well as massage and stretching techniques alongside an understanding of nutrition and exercise physiology which means they can offer good quality advice and management plans for such horses.

One of the biggest management issues for me was organising appropriate low level exercise when I wasn’t available to ride (ie when I needed to work or be away from the farm for a time). I found creating an environment with natural challenges the best approach – I moved to a farm on a mountain with rocks and undulations –

So long before the invention of a ‘paradise paddock track system,’ I accidentally created this for him and his field friend (an elderly and rather rotund pony) by having a local gamekeeper drop hay at the top of the field on his way to feed his pheasants and keeping the water at the bottom so that movement was vital for him.

Prognosis is good for horses with the condition if it is recognised and managed. In one study, 50% horses managed with diet alone improved to within ‘normal exercise tolerances.’

One theory I have read on Swedish Trav sites is that a number of unsuccessful race horses may have PSSM. The prevalence among a range of different other breeds besides those mentioned above isn’t known or researched yet. I recently read an article about American thoroughbred racehorses (flat racing gallop) after which two or three social media comments from veterinary experts suggested PSSM as one of a number of potential explanations for problems in training described in the article.

My point is that this may be a little more prevalent than we thought where horses have been bred more and more for a purpose without genetic testing.

Common management practices of horses living in stable and stall environments may cause a PSSM environment in which horses with a tendency toward the PSSM 2 may develop symptoms because of lack of a natural balance of searching for fodder and moving to do so while running from a few predators along the way.

Track systems and other environmental developments offer a great hope for these horses, while living in a herd (or mini-herd) results in both movement and some social structure with a minimising in unnatural stresses ( herd life of course carries its own stresses)!

One natural response from owners and trainers to seeing a horse that is lame or physically tired is to give them time off in a stable or small paddock. While quite literally‘ what the doctor ordered’ for a tendon or ligament strain, this practice unfortunately does not help the PSSM horse recuperate. It can in fact cause a worsening of symptoms. Once the horse is able to move (during a tying-up period they may not be able to), turn out in a calm environment is the best option with perhaps a friendly and unchallenging companion. (More horses and a larger turn out is built up over time.) Slow hand walking and shorter turn out periods can be introduced in the very early stages of rehabilitation after an extended bout of PSSM symptoms. Return to work will follow a program of rehabilitation exercises determined by the equine therapist/ equiterapeut or equine physiotherapist and veterinary team. Often the veterinary surgeon will take blood samples in the beginning of rehabilitation to establish a baseline (this is especially important in asymptomatic horses diagnosed as a part of DNA testing).

A program may be similar to the following;

Daily light, uncollected work on a lunge-line or under saddle, starting with just 3 – 5 minutes per day at a walk and trot. It is more important to restrict the duration of a single exercise than the intensity.

The duration of work can be increased by two minutes every day. Once they reach 15 minutes of exercise, provide a five-minute walking break after each 15-minute interval of trotting. Continue with this for at least three weeks before introducing work at a canter.

Re-introduction to collected work should also be done very gradually, beginning with just 2-5 minute periods of collection under saddle followed by an opportunity to rest and stretch.

If more than 3 – 4 days elapse without adequate exercise, it is important to start back with just a small amount of exercise and build from the beginning even if the speed of building to full work is more rapid than after a bout of symptoms.

Summary

PSSM1 is a relatively common genetic condition affecting a range of breeds. It leads to excessive and abnormal glycogen accumulation in muscle resulting in stiffness, muscle pain and increased risk of tying-up (exertional rhabdomyolysis).

PSSM2 is an inherited conditionresulting in the same symptoms as PSSM1 but with an unknown genetic origin. It affects primarily warmbloods and Arabians.

Fortunately, PSSM1 and PSSM2 can be managed through diet and regular exercise. Provide a low NSC diet to limit glycogen accumulation in the muscle.

An equine therapist can advise and help throughout the process alongside the veterinary team.

Use fat instead of starches and sugars if additional calories are required. Gradually introduce exercise in short intervals to support glycogen breakdown and decrease the risk of tying-up.

Dietary management can have a significant positive impact on the health and comfort of PSSM horses, and help to minimize the need for costly veterinary care.

Valberg, S.J., Williams, Z.J., Finno, C.J., Schultz, A., Velez-Irizarry, D., Henry, M.L., Gardner, K., Petersen, J.L. 2022. Type 2 polysaccharide storage myopathy in Quarter Horses is a novel glycogen storage disease causing exertional rhabdomyolysis. Equine Vet j. E-pub ahead of print.

Valberg, S.J., Finno, C.J., Henry, M.L., Schott, M., Velez-Irizarry, D., Peng, S., McKenzie, E.C., Petersen, J.L. 2020. Commercial genetic testing for type 2 polysaccharide storage myopathy and myofibrillar myopathy does not correspond to a histopathological diagnosis. Equine Vet J 53(4):690–700.

Valberg, S.J. 2018. Muscle conditions affecting sport horses. Vet Clin Equine 34 (2018) 253–276.