What is it like? This job I do for horses….

The stresses on the horse have changed and grown with competition in equine sports becoming increasingly intense………

In the UK alone there are more horses than there were before mechanisation and the first world war! Most horses do not live as working animals but rather as animals which are required to work sometimes, often with little or no preparation and training for the work they do. These weekend warriors spend all week in a field then are hauled out to jump a course at the weekend or go for a gallop up a hillside alongside others with their human partners enjoying the social opportunity or competition offered by local shows and riding clubs. there is no criticism intended of the owners…we all have horses because we enjoy and even love them and we want to spend what time we have with them having fun and encouraging them also to have fun. My job is sometimes to develop ways in which the horse can train themselves physically while their rider is at work or school. (Anyone who reads my blog will be familiar with my love of track systems in which the horse moves because food and water are spread out over a distance with interesting obstacles in between, this being one of my ways to begin to mitigate the ‘weekend warrior’ syndrome.)

Artificial and forced techniques without careful preparation and after care have become more the norm in the training within a number of disciplines and there are more horses competing than ever throughout the world at lower levels where perhaps the time and knowledge may not be available to their trainers and riders properly to prepare their bodies for the job.

The aim always in working with horses should be to produce movement that is natural and unforced for both rider/trainer and horse. My job can involve helping riders and trainers to see how they can produce that kind of movement through horse-centered, gradual exercises that build the cornerstones and foundations upon which the rest of training and competing stands. Sometimes this can be a job of filling in gaps and undoing old movement patterns that either horse or rider or both have developed, often unconsciously or to compensate for discomforts or injuries.

While at lower levels of competition, knowledge, experience and quality of training may be lacking,, for horses competing at higher levels carry equal and greater stresses with les potential ‘down time’ to recover. Sports therapy has offered much to the higher level equine trainer but time and money constraints often leads to the need to cut corners and aim for quick results.

Horses that I see in therapy often hold the strains and stresses of old injuries long held within their bodies and fascia. With bodywork the horse and owner or rider or trainer and I can gradually untangle a mystery of small stages. While the humans involved in sport can describe their pains and aches in detail and obtain help and training for improvement, their equine counterparts aren’t so fortunate and may have to submit to training in positions and with injuries that nobody knows about (other than the horse himself).

A background in equine psychology and training helps the bodyworker to listen to the horse as much as is possible between species and to fill in gaps by feeling the body and watching for the smallest of clues.

My job may involve seeing a horse work by watching films and advising the humans involved on exercises and massage or stretching that can help. I can meet the horse and their human on the computer or I can meet them in person. My work allows me to put my hands on many horses every week and to learn a little from each one, while helping them to be comfortable in their body. Sometimes I may visit a horse with a veterinary surgeon so that we can work together to look at the horse’s body and make a plan involving pain killing medicines, canges to feeding and exercises for the right kind of movement or even post operative rehabilitation. I may work in cooperation with farriers or bare foot hoof care practitioners and with saddle fitters and dentists. Often my role is signposting the need for a referral (for example when applying some of the fascial moves to the head, it can become apparent that a dental appointment might help). I have to know if a saddle, girth and bridle fit and I can advise on their effect on the horse’s body, often signposting to a saddle fitter or equipment coach. The equine bodyworkers job is as much detective as healer, physical trainer and masseuse.

I have the honour of also working with two bodies as I work with riding horses. Biomechanical gait analysis can be offered using a camera and computer program to the horse or to the parnership between horse and rider and my experience as a riding teacher is extremely helpful to this process. I have to understnad how the physics and biomechanics work between the coordination of two bodies working as one and between the pressures and forces involved in dirving horses and racing in the field of trotter racing. Every day I get to read and learn more and more about the complexities of equine bodywork and physiotherapy but at the same time there is an incredible simplicity in my job.

The first principle is to apply the knowledge I have by listening first to the horse – this is what I teach my students, this is what I come back to every day I work with the horses – LISTEN, Listen, and listen again.

My work can take time, because online i need to observe and ask and observe again and in person I cannot just dive in with a set of techniques

I have to know about machines and clothes that can help and I use a range of machines such as a medical laser, ultrasound and pulsed magnetic field applicator. Deciding what is going to offer the best and longest lasting effect. Considering the horse holistically means my therapy decisions have to be made in the light of a number of considerations, what will be the most cost effective for my owner, while considering the environment the horse finds itself in, the demands on his or her body and the other demands on the owner or sharer and their time. What is available at a race training stable in terms of exercise, underlay and recovery machines may be very different from what is available to a horse who lives and works with logging as his main role or a childs first pony. While the competition horse may have more therapeutic options, he may also have less time allowed for recovery and my plans must take all of this into account. Often this is all going on in my head while I am seeing the horse…… I can be a little tired at the end of the day!

The joy of receiving a call or message from an owner or farrier describing the changes and improvements and of even saving a horse from destruction occasionally by offering a new perspective for training and therapy is fantastic and makes the job wonderful. The opportunity to meet lots of gorgeous, clever, communicative and gentle horses in my week is out of this world and I am enormously thankful for their time and the openness they offer to bodywork.

I am also incredibly thankful to the owners, competitors and trainers that engage my services both online and in person. To be trusted to help a beloved partner and to be able to improve a partnership through my bodywork or biomechanical analysis is a real honour.

Cross training – sports science for you and your horse

Cross-training sounds like something reserved for serious athletes and feels like a bit of an old-school term that’s been around since moms started lacing up their sneaks for step aerobics. But it’s still super-important, no matter if you’re a casual riding club rider, just enjoy a ride in the countryside or a long distance endurance athlete. Cross-training can help build your horse’s and your muscles so that you are both ready for most things.

Yoga for horse riders or Pilates is well recognised as a good way of preparing for our time in the saddle but can we get even more out of a range of other exercises and what about our horse- can we use training from a range of disciplines to better our horse’s performance regardless of our levels?

Obviously I believe we can otherwise this might be a rather short blog post!

So let us begin by looking at the theory of cross training and why athletes that are busy building a career out of one sport might look to train in other sports.

Traditionally speaking, cross-training is what you likely imagine it to be: if you are a runner, for instance, you can throw in some cycling or swimming one or two days per week between your running workouts. Or if you are a cyclist, toss in a strength day and some yoga twice per week to break up the cycling

Proponents (and there are a lot) say that the benefits of cross-training go far beyond what you expect; not only do you balance out some of your imbalances (think cyclists with huge legs and tiny arms or swimmers who are the opposite) but there are a number of health benefits;

1. Fun (at least it should be fun)

2. Keeps you from getting bored with your workout regimen.

3. Allows you to seamlessly adjust your training plan if the weather (or life) gets in the way.

4. Strengthens and conditions your entire body, on many axis/planes of movement.

5. Reduces the risk of overuse or repetitive strain injuries.

6. Allows you to continue exercising parts of your body while the other parts rest.

7. Improves your overall mobility, balance, flexibility, and agility.

8. Builds new proprioceptive and protective pathways in the body

9. Builds bone, muscle and fascial flexibility

10. Protects joints when done gradually and learned correctly

Brock Armstrong a well known personal training guru writes in his article on cross training in 2018;

The benefits of cross-training go far beyond what you expect, and as I will explain, it can actually affect you on a genetic level.

This is interesting and a huge claim for the training form. If we think of a country walk for us or our horse for a moment we can look at how we change the body by choosing different places to walk, different altitudes, different shoes, different company. I have written before that stress cortisol is known adversely to affect tissue and training always to a program with a goal in mind can build cortisol in both you and your horse so let us go back to the country walk-

We walk in company we like or at least are comfortable with – lower cortisol.

We walk in interesting places and take time to fill our souls with views and our stomachs with blueberries or brambles. Our horses sniff and nibble a little new and interesting vegetation and breathe in different air. Every geometry (shape) our bodies assume creates a different load and so a different form of strength, balance or flexibility. Adding hills (both up and down) as well as slopes that challenge our ankles (think of the ankle’s experience walking the sloped shore of a beach) uses our body—and creates loads which in turn changes both our suspending and motion structures but also builds new neural patterns (builds our nervous system). This last is extremely interesting to me as an equine bodyworker.

We can change the pace of our country walk and walk with some friends with children – suddenly it becomes harder work to our bodies as the movement becomes one of short bursts and then slow. Slow movement is harder and takes enormous strength, which is why I often advise horses rehabilitating should walk slowly up steep slopes and over fallen branches to build strength.

There is some science behind all the apparent common sense of moving in lots of different ways and with joy rather than just competitive determination to build a healthy body and improve performance.

Research from 2014 ‘An integrative analysis reveals coordinated reprogramming of the epigenome and the transcriptome in human skeletal muscle after training’ by Maléne E Lindholm et al. Epigenetics suggested that exercise actually changes the shape and function of our genes.

The human genome is complex and dynamic. Depending on what biochemical signals they receive, our genes are constantly turning on or off. When our genes are turned on, they express proteins that trigger physiological responses all over the body, both good and bad.

This is where epigenetics enter the equation. Regular endurance exercise training induces beneficial functional and health effects in skeletal muscle. This study looked at methylation. What scientists call epigenetic changes occur on the outside of the gene, through something called methylation. During methylation, methyl groups (clusters of atoms), attach themselves to the outside of the gene and make the gene more or less able to receive and respond to those biochemical signals.

Scientists know that methylation patterns change when we make lifestyle changes, like eating certain foods (and not eating others), but a lot less was known about how exercise affects methylation. Scientists at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm gathered 23 young, healthy men and women, and performed muscle biopsies on them. They then asked the 23 participants to exercise just half of their lower bodies for three months. They did this by having the volunteers ride a bicycle using only one leg, leaving the other leg dangling there, unexercised. Ingeniously, this turned one of their legs into a “control group,” of sorts. Both legs would experience methylation patterns that were brought on by their normal everyday lifestyle but only the leg that did the pedaling would show the changes related to exercise.

After the one-legged pedalling at a moderate pace for 45 minutes, four times per week for three months, the scientists did more muscle biopsies and calculated the results.

The researchers found that more than 5,000 sites on the genome of the muscle cells from the exercised leg had new methylation patterns. And the genes that were affected are genes that are known to play a role in metabolism, insulin response, and inflammation within muscles. In a nutshell, the genes that were methylated are the ones that affect how healthy and fit we are. Significantly –

The gene changes were not found in the unexercised leg.

This is exactly why cross-training, not only in your chosen sport but in your general lifestyle, and that of your horse is so important. It is also why I am much more interested in tracking ‘planes of movement’ and how fascial chains are engaged that is quality of movement, than I am in how fat or thin or bulked or how much topline I see. These last are important but they do not build a true picture of enduring fitness.

For ourselves and our horses it is good to think of cross training as a method of moving as many limbs, in as many directions, on as many planes as you can. By doing this we build an improved proprioception (knowing where our body is in space) which is vital to adapt to the demands of every form of external bodily challenge.

By targeting new and different exercise we can reduce the anticipatory movements in our horses and build strength rather than confirming old patterns. I will try to give some examples.

A jumping horse who is naturally athletic but never seems to get himself quite to the next level has learned to jump without fully engaging his rear end muscles – he isn’t using the full coiled spring he could. If we train in activities from other disciplines which build that pattern but in a totally new setting we will prevent him using the same pattern again and again. If we don’t we risk encouraging him to practice the same way of getting over a jump and never laying down the new neural pathways and muscle fibres to truly build him for a much bigger and better jump. So we might take him to a western class and learn a few roll backs or we might help a local farmer bring in the cows (believe me chasing bullocks builds those motor muscles), we might choose some fun rides or cross country rides that offer a full out gallop and some bigger jumps or we might work him on a track with big rocks and trees to climb over slowly up a hill. All of these activities depending on horse and rider could be used to cross train the jumping horse. So could swimming, a water treadmill or a walking treadmill. So could a ride in the countryside with other well liked horses and their owners with a few little challenges and changes of pace along the way.

The goal of a cross-training program is twofold: you want to improve your horse’s fitness—both muscle and bone strength, as well as stamina—and provide your horse with some great mental stimulation.

Bones are dynamic tissues; they remodel and change throughout your horse’s life. Even with these changes, repeated stresses can weaken and damage bones. Changing activities can shift the stresses on your horse’s bones and will help to keep bones healthy and strong.

The key to cross-training for both you and your horse is to think about your exercise goals and what compliments them.

To compete in a specific sport, your horse will have to do a fair amount of homogenous training, repeatedly pushing the same physical aspects of his body. Think of doing jump-grid training for your open jumper. That is a lot of jumps! Yes, you can keep heights lower for much of the training, but your horse is still stressing the bones and tissues in pretty much the same way each time he jumps.

Now, throw in some dressage work. Dressage has become very popular as a cross-training sport. There is heavy emphasis on flexibility and coordination. Your horse will have to learn to both stretch and flex, working on extension and collection. Those skills and muscle memory can be very helpful for a jumper. It also shifts the endurance and stamina work over to a different set of muscles—or at least muscles being used in a slightly different way. Bones and joints will be stressed in different ways as well. If you can throw in some fun for the rider too and make them laugh, you can relax the horse while working which releases happy hormones and counteracts stress cortisol. I am serious about fun! It should be that the horse can have fun and some choices within his training schedule is as much a goal of the schedule as all the skills and muscles needed for each competition. We need a healthy partnership with our horses and this comes from having some fun together. Doing, if you will, a bit of team building activities. The trust built in these times offers so much to the psychological well-being of the pair (horse and rider) and that in turn is strongly linked to the success of the partnership and the safety and health of the bodies involved. For most equine sports your horse will also need some endurance and stamina. Even if you just show in pleasure classes, if your horse has three to five classes a day, that is a fair amount of work combined with the stress of being at the event. By the end of a weekend or week of showing, your horse will be exhausted. You could simply build up stamina by doing more and more ring practice. That gives your horse the same physical stressors but does not give him any mental relief.

Changing the tack you are using will also influence different muscles and joints on your horse, and consider a dressage saddle versus a Western saddle—new muscles and joints in your body will be getting a workout too! Think of a horse’s natural state. The horse is outside, not in a stall or confined in a small paddock. He can run, trot or walk at will. The terrain will vary with ups and downs, creeks and rivers may cross his path, as well as fallen logs. The world around him changes every day with the changing seasons and new challenges. I have advocated track systems such as paradise paddock before and once again this kind of movement based living can really help in building your champ (or your elderly cob) a good range of protective pathways in his or her body.

Almost all horses will benefit from doing some quiet hacks and trail rides. Quiet is the key word for me here as it should feel like down time together with your horse. A ride out in the countryside or through the forest is easier on their joints and good for them mentally – and the same for you. By including hills and some water work, you add new physical and mental stressors and build your cooperative partnership. Most horses will splash in a pond or even take a swim at the beach. Swimming is great for building up muscle without stressing joints unduly.

If you don’t have access to trails, at least consider working your superstar on some trail class obstacles. Carefully picking his way through poles on the ground helps your horse with coordination. Walking over a small raised bridge will test his mental capacity as well as his muscles. Throw in some games. Your grand prix dressage horse might find it fun to run or at least trot a barrel pattern from western tradition of rodeo. The same is true of your mellow Western-pleasure mount. Try out the new sport horse football (yes it is a thing) or for a dressage horse where sled carriage is needed and maybe a little self reliance, why not take up mounted archery.

Horses are aware of and stimulated by any changes in their surroundings. Think of how your horse spooked when the tractor at the stable was moved from one field to another! Since mental strength and stability are important for your competition horse, vary your routine on occasion. Change where you work your horse. Even switching back and forth from an indoor arena to an outside ring will give your horse some variation in sights, sounds and footing. Add interesting items to your usual training areas: a balloon tied to the fence or a couple of large rubber balls in the ring can stimulate your horse.

While not specifically sport cross-training, consider trying some clicker work with your horse. Many horses pick up tricks quickly and seem to thrive on the mental stimulation. Training some simple behaviors and tricks can be especially helpful if your horse is on a rehab program and has limited physical activity. Mental workouts can help with boredom and destructive behaviors, too.

From your horse’s perspective, the more you can round out his training, by providing varied physical and mental stimulation, the sounder he will be. I have recently read in a Facebook thread or two a couple of terms ‘ring sour’ or ‘loss of work ethic’ describing horses that no longer enjoy competing, and honestly I have seen a similar attitude in the occasional human too. With some effort on our parts, we should be able to keep our equine partners and us happier and healthier with a true cross-training program and some imagination.

Build your partnership

Strengthen the mind

Strengthen the body

Please contact me for help and ideas about cross training or join my happy healthy horses community for more tips and tricks!

I was recently asked what is the longest time a horse can or should go without food;

It is tempting if you have fat horses and ponies to give them small amounts of fodder so that in fact they spend long periods of time with no hay or haylage.

A “weight control diet” is not one in which we swing from starvation to gorging – this is in fact a habit or behaviour in humans which we recognise as unhealthy. But it can be important for a pony to lose weight and whereas most horses worked on farms and even in cities pre the lat world war, now they are often weekend warriors doing daily little all week then going out to compete, undertake lessons or just go for long country rides at the weekend.

We need to feed regularly and horses need access to hay or grass or similar pretty much around the clock but we also need to be careful to know why our horses are eating and how this compares with how much they need to work to get at that food.

First a salient question might be;

‘how long can a horse be without food before damage is done and secondly, ‘if they don’t eat for longer than that time, what damage is done?’

– 4 hours, maximum is the answer to the former.

Why?

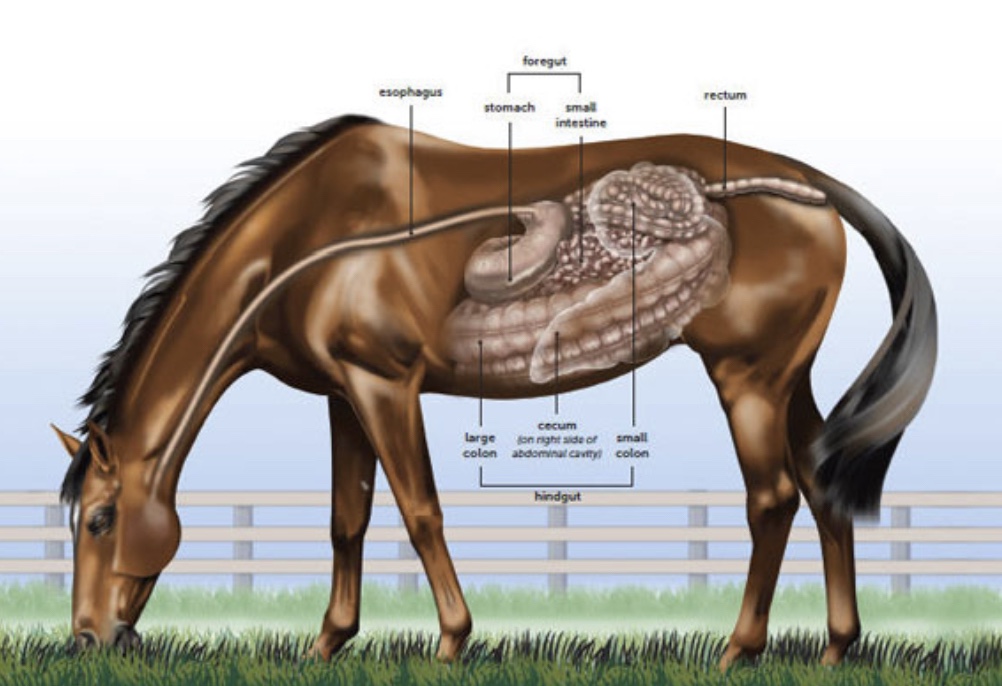

Horses are grazers. They are designed to eat constantly. They have no way of storing their acids and digestive enzymes, they’ve never needed to. They have no gall bladder to store bile and their stomachs release acid constantly, whether or not there is food in the stomach and intestines.

A horses stomach only holds approximately 8-15 litres. Depending on the substance eaten, it takes on average 4-6 hours for the stomach to completely empty. After this, the acids and enzymes start to digest the inside of the horses stomach and then the intestines. This causes both gastric and intestinal ulceration. It has been estimated that 25-50% of foals and 60-90% of adult horses suffer from ulceration. I won’t go into detail here about this, there is a lot of information about ulcers available on the internet, but I am noticingmore and more horses with ‘uncomfortable undercarriages’ in my bodywork. No manner of massaging and stretching the outside is going to remove sores and holes on the inside, so I am often referring the owners onwards to get help for sore tummies so I can get on with helping the muscles, fascia, joints, tendons and ligaments do their job to the best they can!

But ulcers are not the only concern for a horse left for a time longer than four hours without food.

Having an empty stomach is a stress situation for a horse. The longer they are starved, the more they release stress hormones, cortisol predominantly. Cortisol blocks insulin and causes a constantly high blood glucose level. This stimulates the body to release even more insulin, and in turn this causes fat tissue to be deposited and leptin resistance. Over time this causes insulin resistance (Equine Metabolic Syndrome is an example of this). All of these mechanisms are well known risk factors for laminitis (fång) and are caused by short term starvation (starting roughly 3-4 hours after the stomach empties). Starving a laminitic is literally the worst thing you can do. Over longer periods, this also starts to affect muscle and can cause weakness, and a lack of stamina so performance horses also need a constant supply of hay/haylage to function optimally.

Let’s not forget horses are living, breathing and feeling animals. We talk about this stress reaction like it’s just internal but the horse is well aware of this stress. Door kicking, box walking, barging and many other stable vices and poor behaviour can be explained by a very stressed horse due to food deprivation. Try not to be irritated by a horse that dives for their net, remember their body is genuinely telling them they are going to starve to death. They know no different.

But surely they spend the night asleep so they wouldn’t eat anyway?

Not true. Horses as prey animals, only need 20mins REM sleep every 24 hours so they can keep a watch for predators and be ready to run. They may spend a further hour or so dozing but up to 22-23 hours a day are spent eating. So if you leave your horse a net at 5pm and it’s gone by 8pm, then by 12am their stomach is empty. By 4am they are entering starvation mode. By their next feed at 8am, they are extremely stressed, physically and mentally.

Now I know some fat horse and pony owners are reading this mortified. I can almost hear you shouting at your screen “if I feed my horse ad lib hay he won’t fit out the stable door in a week!!”

Studies suggest in fact that a horse with a constant supply of hay/haylage will eat far less than the same horse that is intermittently starved. (They likely don’t eat in a frenzy, reducing the chance of colic from both ulcers and over eating. Chubby ponies included.)

However I’m not suggesting you sit your chubby cob in front of a bale of haylage and say have at it! Firstly, feeding a constant supply does not mean ad lib feeding. It means use some ingenuity and spread the recommended amount of daily forage so the horse is never stood with out food for more than 4 hours. I am not promoting obesity, quite the opposite, feeding like this reduces obesity while also reducing the pain and discomfort of sore stomachs. This can be done whilst feeding your horse twice a day as most horse owners do. Just think outside the box for your own situation. There is a difference between ad lib and a constant supply. There is much we can do to reduce calorie intake and control weight whilst feeding a constant supply.

The easiest is small holes nets. There are many. Trickle nets, greedy feeders, nibbleze, trawler nets etc. Remember, you can give a normal net and one of these for them to nibble at after.

A few other tricks,

Hang one of the nets from the ceiling/rafters, it’s harder to eat out of a net that swings – check with your physio or bodyworker that there are no contraindications from neck or thoracic issues.

In cooler climates you can soak the hay (a minimum of 4 hours to be effective in reducing the calories).

Mix with straw but be sure to introduce the straw slowly and make sure it’s top quality and a palatable type eg Barley or Oat, otherwise they won’t eat it. Don’t use rye straw and in water countries check your straw is low calorie (peanut may be a higher calorie than your local hay for example).

Don’t forget exercise.

Try to create a track system where the horse needs to move between different places for food and drink. You can add in ‘natural’ obstacles that mean he effectively goes over cavaletti sized bits of wood as he travels between places to get food or water or has to put his front hooves up on something to get to a net, creating a stretch opportunity (those of us that have tried Pilates or yoga know how well the body responds to toning the muscles – lean muscle burns calories quicker).

The best way to get weight off a horse is exercise. Enough exercise and they can eat what they want! But since most of us do t have the luxury of riding our horses or even putting them on exercise machines for much of the day, every day, we need to create environments which help the horse to work and use their body while we are away working to pay for the hay!

Try to lay off the bucket feed and treats! Horses on a diet require a vitamin supplement in the form of a balancer but that’s it. The odd slice of carrot, apple or swede won’t do any harm but the average horse does not need licks, treats, treacle, molasses, cereal based foods. Even food bags that offer low sugar or the very misleading “No added sugar” tend to have more calories than a horse in light work requires. Obviously if your horse is trotter racing and training every day or regularly competing in eventing he is going to need extra calories compared with a cherubic Welsh pony with a penchant for breaking into the neighbours orchard an very little other demands on his calories (yes i have a pony in mind – you can meet him on my Instagram)! Your horse is better off with a constant supply of hay, salt lick and a good balancer.

The use of hay nets in the UK and europe is relatively common. I’d estimate 95% of horses I used to see were fed this way and maybe 50% here in Sweden. Very few horses eating from hay nets re reported in research as having incisor wear or neck/back issues as a result though if your horse already has problems you might want to look at slow feed balls or other options to avoid exacerbating existing issues.

Feeding from the ground or boxes just off the ground in frozen situations is ideal, but a constant supply seems to trump this in terms of horse health.

Finally, straw can be fed to horses safely, introduced very slowly, with fresh water always available, plus a palatable and digestible type of straw which will depend on your area.

Just a little note on transporting horses; please remember to feed your horses during transport! I am astonished when I see horses without this calming and regulating option. Even if it’s a short journey remember your horse doesn’t know that so stress at not having available food can set in quite quickly!

Chewing helps most animals calm down as it has a regulating affect on the central nervous system. (We chew our nails when nervous and gum to stay awake and calm. When I have dogs in the swimming pool who are nervous, chewing a treat can often reduce the pulse and allow a better breathing pattern when swimming). Hay chewing is just the same so we can give our horses a hay net to help them while waiting for the farrier or vet (providing of course it isn’t contraindicated by the situation) and keep them calm while away from the herd.

So just in summary I am making a plea for regular feeding with no breaks of greater than 4 hours for the sake of our horses’ insides!

The balanced horse

We can easily assume that horses know where their feet are, how to stand on them and use them for balance and propulsion. You don’t give much thought to how they sense the ground through their hooves; you simply assume that they do because, after all, within hours of birth, horses can stand and run.

A horses’ quality of movement is directly affected by how they place their four small circles of surface area (4 feet) on the ground. Horses have habitual (unconscious) patterns of standing which research has shown they develop from the first day they start eating grass (there is usually a favoured foot which goes in front when eating and this one has a slightly different hoof wall shape until/if we choose to reshape for metal shoes and through barefoot trimming).

Similarly each horse develops their own pattern of moving without and then with a rider or harness and ‘kit.’ This new pattern of movement can create anxiety, instability, poor quality movement and what we typically think of as “resistance” as they attempt to remain upright especially in biomechanical relationship to their rider or the harness and vehicle/machinery they pull. It is the job of the first riders and trainers to prepare their horse for the mechanical stresses abs strains of their job. Sadly all trainers are not equal in terms of experience and skills in this area and so there are variable results for the horse.

Many classical trainers in fact train a large majority of movements from the ground and without the weight of a rider- this allows horses to develop independently in their proprioception and movement before adding the complexity of weight. Some systems (such as the Spanish riding school in Austria) build the horse’s ability through levels of rider and trainer, ensuring their riders have a balanced and independent seat before beginning. The majority of horses and ponies do not have the benefit of hundreds of years of training experience such as is available in some of the great military schools. When we buy our own ‘finished’ riding horse, we cannot guarantee how he or she has laid down their muscles and depending on their experience and where they have lived, they can have very specific proprioceptive problems.

My old riding horse Joe came with an amazing ability to go very fast across fields and jump fences but he had little idea how to negotiate steep hills. When he moved to my farm in Wales, he not only had to take me for rides up and down steep hills but also to stand and eat on slopes. For the first few weeks we noticed he had a lot of bumps and strains until one day I saw him effectively fall off the hill he was standing in and roll down the field to the bottom where there was a flat area. He had lived on flat paddocks, worked as a racehorse on race tracks which were usually flat with a few big fences (which he cleared with ease) and he had tried and been successful with low level show jumping in his retirement from racing. What he had not down was climb hills and he had never stood side on to a hill to eat. He learned and he stopped falling off the hill within a matter of four weeks but his difficulties demonstrates how proprioception is an essential part of safe movement.

By contrast our highland pony lived wild for the first few years of his life on the craggy and uneven ground of the common grazings on the Isle of Skye. He is one of the most sure footed horses I have ever encountered. He has a remarkable ability to get in and out of places and to know what needs to be jumped and what can simply be kicked out of the way! (An ability that wasn’t always helpful to the young girls that tried to take him over a series of flimsy jumps in their riding lessons!)

Meggy was a pony who refused to go in her owner’s rather lovely lorry. She had been transported prior to sale with ease in a cattle trailer with a long and relatively low ramp but in a cattle trailer that was all metal and really noisy. Yet she had gone on with ease. The beautiful, comfy and quiet lorry was a different matter. She viewed it with apparent suspicion and distaste, fighting with all her little frame to avoid putting a foot in the ramp. Simply forcing her resulted in rearing and digging her little feet into the ground or worse lying down on the bottom of the ramp. When I broke down the problem, she could go in all sorts of boxes, stalls and trailers. She could walk over bridges with relative ease and a little persuasion. So the biggest issue was the steepness of the ramp and her ability to work out how to negotiate it. By working on her balance and gradually increasing the ramps gradient (using other ramps up to the lorry ramp) eventually she learned how to organise her legs to get up and on the lorry which she then showed she loved!

What is proprioception? Imagine running upstairs with a basket full of washing where you cannot see your stairs or your feet. How do you know where to put your feet and how to hold your body? Small sensory balance nerves from joints, muscles and skin gove messages to your brain which keep you upright. When you learned to negotiate stairs as a child, you probably had to use your bottom, your vision, your hands in order to feel safe until you built the skills and the muscle memory for the job and at that point you flicked a switch over to automatic and relied just on proprioception alone to do the job.

A horse gets up on his feet pretty quickly as a foal so he can run from predators and keep up with the nomadic lifestyle of his species, but he does not learn how to use those same legs to do the things we humans require him to do nor to move while wearing the weights that shoes or boots create on his feet nor to hold his back and stomach in a way that protects his spinous processes and prevents problems like kissing spines that arise from not understanding how to carry the weight of tack and/or a rider. These things require training and the development of new neural pathways and new patterns of muscle memory. If some of these patterns are lacking, we as owners and bodyworkers or horse trainers can begin to fill in the gaps to create beautiful movement and to shield our horse’s bodies against injury.

How the horse’s foot meets the ground is how that horse meets the world. No matter the size of the horse, his relationship to gravity and the earth is dependent on the way the horse stands and lands on his hoof.

While many people recognize that good quality shoeing and trimming are essential parts of good horsemanship, in almost all cases training attempts to alter behavior and movement of the horse without addressing the fundamental way the horse’s foot meets the ground. Increasing numbers of anecdotal case studies suggest that, while it may be the case that the well- trimmed barefoot horse has a little better sense of what is going on under him in terms of protecting his feet, he can have just as many bad habits in his body in terms of carrying a rider or pulling a cart.

In the field of human and dog physical training we already have a bodywork and development mode that we know is extremely successful in building the core muscles and improving proprioception and results int terms of clinical and performance outcomes.

Within the equine barefoot trimming field we have been experimenting and demonstrating excellent results by using different surfaces and challenges with physical obstacles on paradise track systems and in horse walkers.

I have been ‘playing with’ using similar balance exercises to the balance cushion exercises I use with dogs and have seen some interesting and promising results in both performance and elderly horses alike. I have been experimenting with placing a slightly unstable surface under horse’s feet and offering them slight movements such as reaching a little to one side or another for a piece of carrot or gently massaging one shoulder/hip or the other and creating a small wave of movement within the body.

As a riding instructor/clinician and trained equine bodyworker with a reasonable understanding of biomechanics, anatomy and physiology, I have been looking for specific equine research to explain why this seems to help and my conclusions are drawn from human and dog studies as there seems to be relatively little in the equine area. There appears to be activation of the proprioceptors in the feet of the horse, which likely send new information into the cerebellum, the part of the brain that regulates balance, posture and motor learning. This happens when any horse goes over any new surface. There is a change in the autonomic nervous system, the part of the nervous system responsible for bodily functions not consciously directed such as breathing and heartbeat. More importantly, sensory integration theory from the human field suggests that the horse learns for himself how to alter his balance, movement, then his emotion and thinking states.

The horse experiences a switching back and forth in his nervous system from the sympathetic (flight and flight reflex) to the parasympathetic (grazing reflex).

I often see horses shift from apparent anxiety or agitation to calmness during a balance session and reports from owners suggest that this ‘thinking state’ can remain with the horse for several days or weeks after a session. Generally techniques that alter a horse’s behavior and movement are a result of external training and rote learning and not necessarily of the horse’s choosing. This calmness is similar to what can be achieved with children with sensory integration problems who are often much calmer and better able to think in school after occupational therapy has offered sensory integration training (a considerable amount of balance and pressure exercises are often involved) or within my own work with street dogs and anxious dogs in which sensory integration training through proprioceptive walkways and balance exercises seems to offer the dogs a bravery and self confidence they lacked before training.

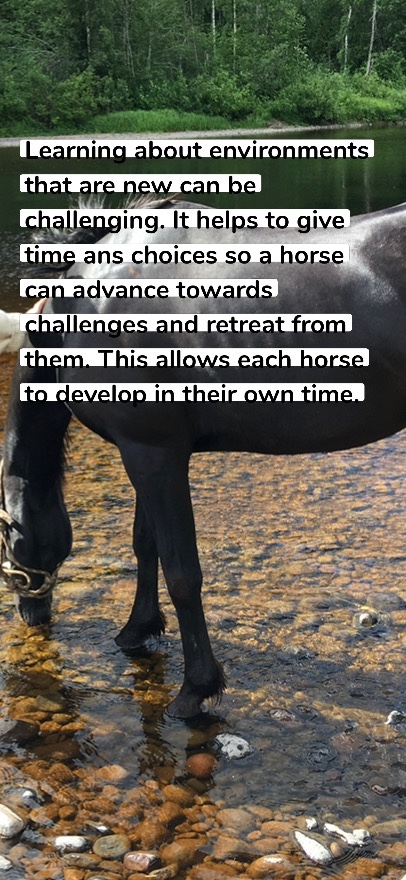

Proprioceptive training can include other exercise such as walking over challenging surfaces slowly (slowly is key so the horse has time to process the nerve information he receives). I have worked with tarpaulins, small riverstones, water, sand and even deeper snow by going slowly and changing the angles the horse works at, the mechanical structures of the horse (muscles, fascia, ligaments and tendons) can be activated safely.

Horses will tend to want to rush over perceived unsafe surfaces or even jump them. It is essential to have a trusting and non-forcing relationship as well as enough time to allow the horse to think about and decide whether or not to undertake a task. ‘No’ has to be an ok answer in therapy. I can say no to my physiotherapist or trainer, as a human, because the challenge is mentally or physically too great. The trainer/physio then has to re-present the challenge either changed so I can cope, graded so I can cope or completely altered so it doesn’t have the same effect on the mind. It shouldn’t be any different for the horse. As a human trainer I can explain and suggest or even persuade my riding clients things they can try. My approach needs to be the same with horses. In my opinion force has no place in my work but clear explanation and adaptability on my part has.

In my rider training I also work with balance and proprioceptive activities. And with riding lessons it is interesting to play with not managing the horse’s movement directly and especially after a time on balance cushions. If the horse stands on the cushions both without and then with the rider for a time before being offered the cue to move away at their own pace and without needing to be in a ‘frame’ or with very much contact, they often appear to seek and find their own balance. This is fascinating to me. Under normal training, some horses seem to look constantly to their rider for micromanagement while, after balancing, being encouraged to move at different paces in a safe environment with good footing and fences such as a round corral or school (these latter are for the rider’s safety by having fences which allow me to control the pace if needed), and without over management from the rider or me, they are offered time to explore how the new neural information gained from those balance exercises can help them move comfortably at the gait requested. Essentially this is more ‘horses with choices’ ideas as we offer the horse information and then give them the chance to explore it, rather than determining their frame or how they should use their muscles.

I find it particularly interesting with older horses who already have well set (though not always healthy) patterns of movement. The approach is extremely gentle and fits with my strong sense of ‘do no harm’ in older horses.

I tend to be very careful about stretching work with older horses. This subject is for a future blog however, I know for myself with my odd pattern of movement from disability and injury as a child that simply removing my muscle knots and stretching overly tight muscles to within a ‘normal’ range is painful and unhelpful while adjustments I have made semi-unconsciously myself through yoga, balance work and proprioceptive awareness stays with me longer and pain is experienced only as the ‘normal’ discomfort from training and reshaping muscle fibres!

Working with carefully graded balance-challenges seems to improve range of movement in some of my older clients and I am interested to extend this and look at the results. I’d love to think that the improvements we see in human and dog movement through working with balance and gentle stretching can be mirrored for our horses.

Over to you….

Have you worked with your horses proprioception or balance? What kind of things have you tried?

Would you like to know more or to work with me to improve movement in your horse, yourself or even your dog? Please feel free to contact me as I can and do work remotely as well as in person (the recent health restrictions internationally have taught us all just how much can be achieved online and I have seen some fantastic results even without being ‘there,’ with my clients and their animals!)

An essential muscle

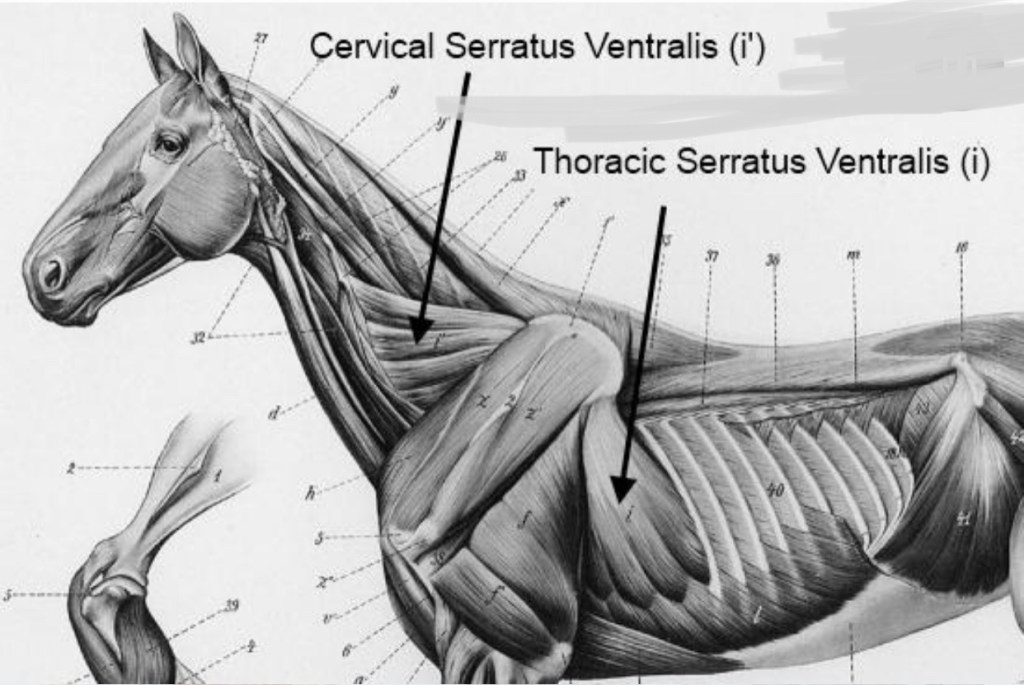

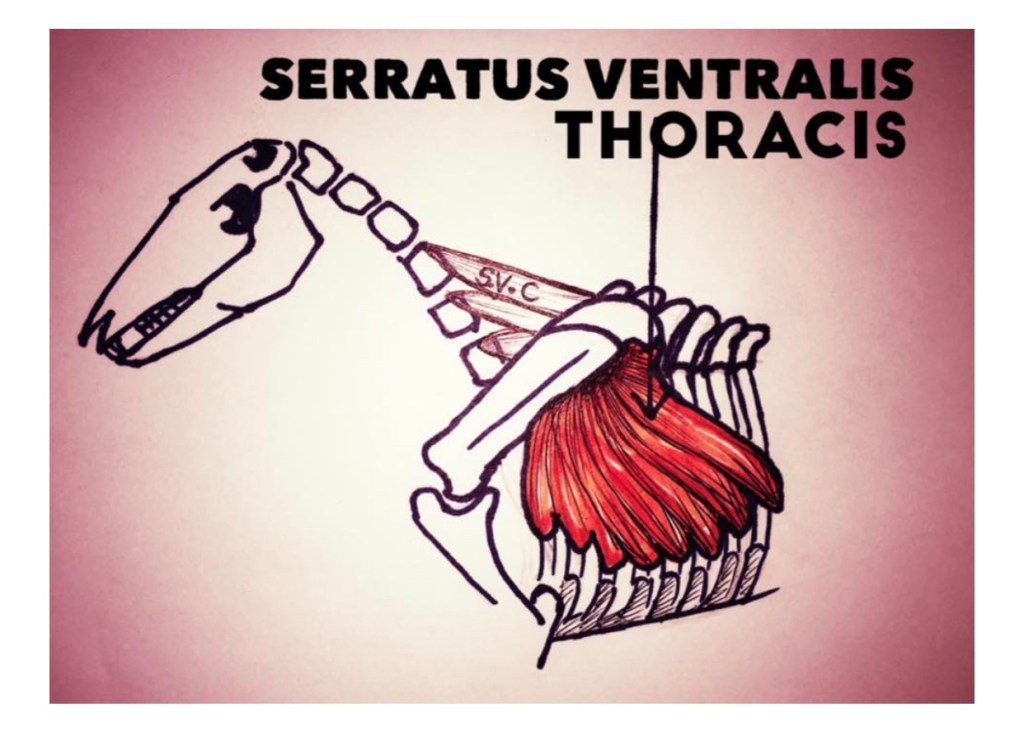

SERRATUS VENTRALIS THORACIC (SVT)

The SVT is the second part of the Serratus Ventralis muscle.

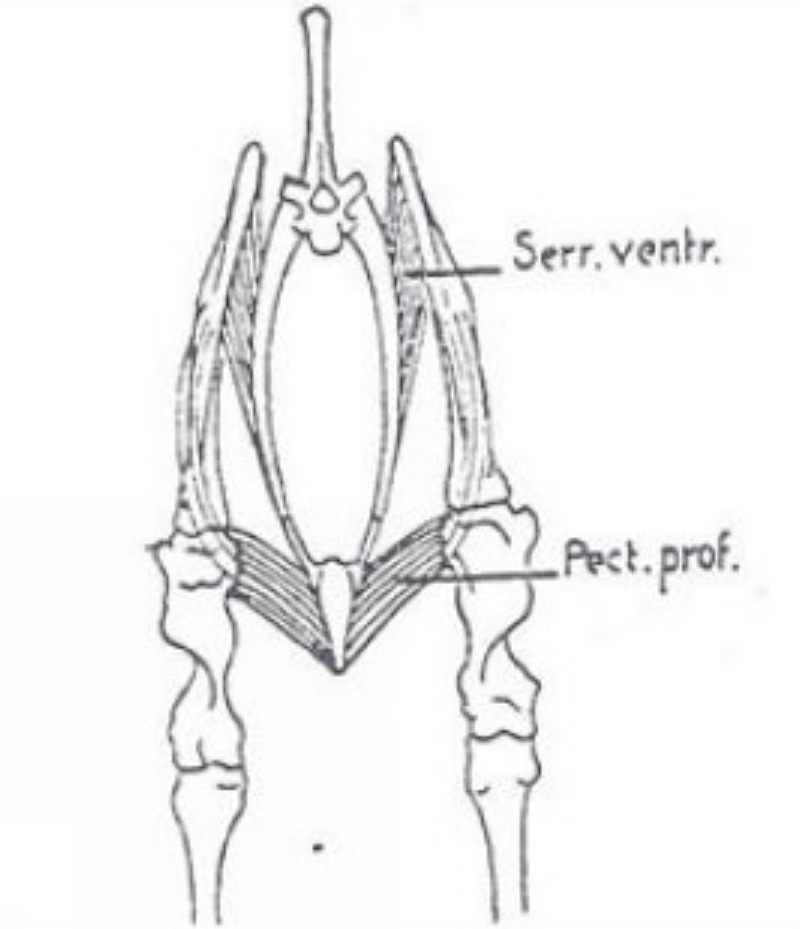

It is one of the deep muscles of the body and really essential to the horse’s movement. Serratus Ventralis is an essential muscle of the thoracic sling, supporting the weight of the neck and thorax from its position on the medial aspect of the scapula. This muscle is again divided into a cervical and thoracic portion, with the cervical portion originating on the transverse processes of C4-7 and the thoracic portion originating on the 1st to 8th ribs. Both portions insert on the medial aspect of the scapular cartilage and are innervated by the ventral branch of the local spinal nerve and the long thoracic nerve. The Serratus Ventralis Cervicis is much thicker than its thoracic counterpart. It extends along

the horse’s neck and draws the upper part of the shoulder blade forward. It can become hypertrophied or more pronounced in case of lower limb trauma, when extension of the front limb is diverted to the trunk muscles.

Indirectly, both serratus muscles are also very important for proper functioning of the horse’s stay apparatus as they aid in sustaining the horse’s weight when the muscle bulk relaxes. It should be considered in horses that do not appear rested that the stay apparatus and the thoracic sling apparatus should also be looked at in a wholistic diagnosis process.

The serratus ventralis thoracic is the section of the muscle that is located behind the shoulder in the region of the thoracic vertebrae as the name would suggest.

The Serratus Ventralis Thoracis attaches the inside of the horse’s scapula to the ribcage and can be intimately linked to the External Oblique. It is linked to breathing functions because of its position.

It inserts into the shoulder blade and attaches into ribs 1-8/9.

(Ribs 1-8/9 ——> Medial Aspect of the scapula cartilage)

What does it do?

• Draws the the scapula (the shoulder blade down and back, playing a part in extending the limb.

• Is part of the “Thoracic Sling” which suspends the horses chest cavity from the forelimb.

The forelimb of the horse is very different from the human and not just because the foot is encapsulated by a hoof! The horse doesn’t have a collar bone like humans, but instead relies on muscle known as a synsarcosis to hold the thorax and forelimbs together. This muscular ‘joint’ affects the kinetic chains and fascia of the entire horse. A dysfunction in this area can be highly detrimental to the whole body.

Contraction of the thoracic sling muscles lift the trunk and withers between the shoulder blades, raising the withers to the same height or higher than the croup (hind end). By contrast, a horse that is travelling without proper contraction of its sling muscles, or with weak sling muscles will appear downhill and be ‘on the forehand.’

The large serratus ventralis thoracis as well as its cervical elements are well adapted for the task of carrying the trunk between the forelegs and their job extends to more than moving and connecting the front legs to the thorax, but even to the action of the horse’s spine.

• Thought to contribute to the elastic properties of the forelimb.

. As part of the thoracic sling, it is a part of the process in which, as the neck lowers a little (within the normal range of movement and not with overbend), so the serratus ventralis comes into play, supporting the thorax and enabling the back to raise (as described in the dressage term ‘engagement’).

It is a vital muscle in both the extension of the front leg and the movement of the back when being ridden or engaged in athletic movement.

Main causes of problems in this muscle:

Injury/strain through poor tack, lameness, direct trauma (falling onto shoulder) and discipline, however it can also be affected by hoof growth or poor foot care..

For example:

• Discipline:

Jumping disciplines could predispose injury to the SVT due to the large concussive forces of landing that will increase the demand on the SVTs role in supporting and suspending the trunk from the forelimbs.

Tack:

Ill fitting saddles that restrict shoulder movement, (i.e too tight) can prevent the scapula (shoulder blade) from moving back through direct restriction and/or pain which could result in SVT weakening.

Over girthing or poor girth quality can directly impair the SVT through pinching and direct pressure that ultimately results in pain, injury and tension.

• Lameness:

Chronic offloading of one forelimb to the other unilaterally increases the demand of the SVT in suspending the trunk thus, exposing it to abnormal strain.

What might you see in your horse to suggest a possible problem with the SVT

As well as the way the horse is travelling (ie downhill )there may be other signs that your horse is tight, sore or weak in the Thoracic Sling muscles.

• Reduced forelimb stride length.

. Reduced shoulder extension & flexion.

. Poor respiration (Due to location of the SVT over the ribs tension & pain could hinder ribcage expansion).

. Poor turning particularly on the forehand.

. Refusal to jump.

. ‘grumpy’ to be tacked up / sensitive to the girth

. breathing problems; even appearing to hold their breath in canter or gallop so dropping out of that gait

. reluctance to have front feet picked out / stretched forward for the farrier

. difficulty going up or down hills

. reluctance to pick up a lead or tend to swap leads or cross-canter

.difficulty with banks, drops and other jumps or obstacles that require extra “reach” in front

. showing reluctance when asked for lengthened strides

. tiring more quickly during exercise, because of having to work against the tightness to go forward

So what to do next –

If you suspect a problem in your horse’s SVT you might talk first with an equine vet together with an equine bodyworker. It would be important to rule out any nerve damage and to check both sides of your horse for muscle damage. (Horses can sometimes throw a little extra weight across if both front legs are sore so that it becomes difficult to see which shoulder is the origin of a problem).

You can quite easily feel the superficial pectorals and serratus ventalis thoracics yourself to see if you think your horse may be tight here:

Gently run your hands over the surface of the skin and see how they feel. It is good to go over your whole horse so you have the possibility of comparing different areas of muscles. Are they:

* Tight

* Loose

* Consistent and smooth

* Bumpy and stringy

* Are there even holes or dents in the muscles

* Is your horse sensitive in the chest or girth area

If you think your horse may be sensitive or tight in this area, or lacking strength and muscle tone, Equine bodywork or physiotherapy. is a great way to detect and treat problem areas helping to free up your horse, make them more comfortable and therefore more able to work correctly and become strong.

This isn’t a common area of unjustly although it can often be insufficiently built for the job a horse is expected to undertake and tack can adversely affect its development. Driving horses also risk both injury and underdevelopment of this muscle and it is a muscle known to be prone to injury if tired or over worked.

Physiotherapy will look at both electro therapy modalities; laser, pulsed magnetic field therapy and ultrasound alongside massage and remedial exercises such as slow walking, weight shifting, balance work, long lining and slow pole work. A physiotherapist or hydrotherapist may also recommend work on an underwater treadmill at a slow walk and with the support of the water.

Prevention is always better than cure and there are a number of things you can do and look at to give your horse the best possible chance to have strong muscles for a lasting career and healthy life.

The stronger and healthier the muscle is the less likely it is to become injured. Correctly warming up and cooling down the muscle will also reduce injury risk, and this can be a simple addition to a horse’s training plan with a good amount of walking in hand or on long lines as a part of daily training and especially when coming back into work after a testing period. Having your horse’s saddle checked is of course vital but don’t forget their girth which can affect and injure the muscles if ill fitting or the wrong shape for your horse. With a greater research and understanding in this area has come the invention of a range of ergonomic girth’s and your equipment specialist or saddle fitter together with your equine bodyworker should be able to help you decide on the most appropriate girth for your horse and their discipline.

An important aspect of fitness training is ‘cross-training’ – so as not to only concentrate on developing the key muscles used for your particular sport, but also in developing the stability muscles required for postural strength. Many concepts in developing these postural muscles are drawn from both yoga and Pilates and can be applied across to the horse (even though he has four legs and not two)! Both yoga do Pilates recognise the need for cantering or developing a strong core. This together with body awareness or proprioception are two of the base areas of development for fitness and training for any discipline. Research in human athletes has shown that strengthening these muscles enhances athletic performance and reduces the incidence of injury. It has also been shown to be a very effective exercise program in accelerating the post-injury rehabilitation process in humans. In the horse the trainer needs exercises which aim to improve ‘core stability,’ ‘flexibility’ and ‘coordination.’

The presence of incorrect movement techniques can result in the inability to undertake a movement with maximum efficiency or with the least expenditure of energy.

A thoracic sling lift reaction can be used in a healthy horse who is happy to take part in it;

apply steady but gentle pressure with your finger starting at the sternum, sliding back over the pectoral muscles to an area to behind the girth. The horse will respond by lifting through the withers. This will activate the thoracic sling and the abdominal muscles. The lift should be held for about 5 seconds, then released. This stretch can be repeated 3 to 5 times as part of a stretching routine which might also include carrot stretches between the front legs and upwards with the head raised. As with most yoga or Pilates exercises, carrot stretches have the greatest effect when done as slowly as possible and held in place for as long as possible – about 5-10 seconds. Exercises for horses to strengthen the core stabilizing muscles can not only be used as part of a regular training program to enhance performance and reduce injury, but may also help to prevent the recurrence of back pain or problems with other muscle groups such as the thoracic sling in some horses who have suffered weakened or injuries in these areas.

For basic equine bodywork and full physiotherapy courses contact me through my website http://www.fyrafotter.se

Acclimatise your horse to scary or new environments

Using essential oils as a part of your horse’s care

Aromatherapy is a holistic healing treatment that uses natural plant extracts to promote health and well-being. Sometimes it’s called essential oil therapy. Aromatherapy uses aromatic essential oils medicinally to improve the health of the body, mind, and spirit. It enhances both physical and emotional health.

Aromatherapy is thought of as both an art and a science. Recently, aromatherapy has gained more recognition in the fields of science and medicine. Essential oils are composed of chemicals extracted from plant leaves, stems, wood, bark, and/or fruits. Together, these compounds are classified as secondary plant metabolites, which plants produce to survive in the environment. Unlike primary metabolites, secondary metabolites do not participate in basic life functions such as cell division and growth, respiration, storage, and reproduction. Instead, secondary metabolites protect the plant in some way (e.g., against insects, disease-causing organisms, and the sun’s ultraviolet rays).

The list of available essential oils is extensive. Some of the more commonly used essential oils in modern medicine include basil, bergamot, chamomile, devil’s claw, eucalyptus, frankincense, geranium, ginger, lavender, lemongrass, peppermint, tea tree, valerian, white willow, and yucca.

The first medicinal drugs came from natural sources and existed in the form of herbs, plants, roots, vines and fungi. Until the mid-nineteenth century nature’s pharmaceuticals were all that were available to relieve man’s pain and suffering….” Jones AW Drug Test Anal. 2011 Jun;3(6):337-44. doi: 10.1002/dta.301.

Some essential oils are known to have multiple benefits, like lavender. It smells beautiful and yet has a number of uses. In fact, lavender is considered the most versatile of all oils because it:

• Calms

• Cleans scrapes

• Reduces itch for insect bites

• Reduces nausea

Relieves allergies Some of the uses for essential oils with horses include:

• Repels insects

• Reduces anxiety

• Strengthens immune system

• Reduces inflammation

• Speeds wound healing

• Increases energy

• Improves digestion

• Relieves pain

• Increases circulation

While we can make up rubbing oils for example for insect repellents we can also apply the principles of zoopharmacognosy and offer oils in such a way that our horses can select their own oils. This technique is useful where oils are being offered to ease psychological or change behavioural issues. Zoopharmacognosy is a behaviour in which animals apparently self medicate by selecting and ingesting or rolling in plants, minerals or insects and psychoactive drugs to prevent or reduce the harmful effects of pathogens and toxins.The term derives from Greek roots zoo (“animal”), pharmacon (“drug, medicine”), and gnosy (“knowing”). An example of this in horses is when we see horses in the UK working h the sir way down a hedgerow where wild willow or hawthorn and other flowers and herbs are available and selecting some. My old horse often ate rosebay willow herb at the end or if allowed in the middle of a longer endurance ride – years later I discovered it has an anti- inflammatory action and I suspect he was self medicating to cope with the rigours of his & my sport. An example of zoopharmacognosy occurs when dogs eat grass to induce vomiting. However, the behaviour is more diverse than this. Animals ingest or apply non-foods such as clay, charcoal and even mild amounts of toxic plants and invertebrates, seemingly to prevent or relieve parasitic infestation or poisoning. The problem with the theory is that while numerous behavioural examples are noted in zoological texts, it is hard to research under laboratory or more stringent conditions. Anecdotal reports from many naturopathic practitioners however offer examples both in the wild and of animals self selecting in domestic situations where choices are offered (eg willow or wilted nettles cut and out into a paddock; rosehip shells in a bucket; even our salt stones are examples offered in zoopharmacognosy texts. This term first appears in literature in the late 1970s and gained popularity from a number of academic works and in a book by Cindy Engel entitled ‘Wild Health: How Animals Keep Themselves Well and What We Can Learn from Them.’

Offering oils separately and at a distance from your horse (eg in the corner of a stable or in a round corral) where the horse is freely allowed to move away from them can be very helpful. This is also useful where you intend using an essential oil topically or on yourself – some horses, like some humans simply seem to dislike some smells. It may be by association as we experience (a friend of mine hates lavender – due to numerous visits to elderly persons homes with her vicar father as a small child, she thinks!) or simply preference.

In vitro (laboratory) study results show some essential oils have marked antimicrobial activity against both bacteria and fungi (Ebani and Mancianti 2020). This includes multi-drug-resistant strains of bacteria such as Pseudomonas spp. and Staphylococcus spp. Essential oils not only have bactericidal properties, but some reportedly also exert antibiofilm properties. Biofilms are conglomerations of bacteria and the protective “slime” they produce that forms an impenetrable barrier around disease-causing organisms.

Essential oils also show promise as insecticides. One study demonstrated that tea tree oil extracted from Melaleuca alternifolia had excellent in vitro adulticidal activity against stable flies (Dillmann et al. 2020). These blood-sucking flies are a nuisance to horses, interrupt feeding, and can induce a flight response due to their painful bites (even in the middle of competitions). Biting flies can also transmit diseases, including equine infectious anemia.

Another group (Cox et al. 2020) reported that a commercial herbal topical spray used once daily for 28 days appeared to effectively manage insect bite hypersensitivity. The spray included extracts from lemongrass, peppermint, camphor, may chang, and patchouli. These essential oils were selected due to their previously demonstrated immunomodulatory (alters the immune response), antihistamine, antipruritic (anti-itch), anti-inflammatory, anti-allergy, analgesic (relieves pain), and larvicidal (kills juvenile insects) activities.

One published study also supports lavender’s widely accepted role as a calming agent when used as aromatherapy, as determined by decreased heart rate variability in eight dressage horses (Baldwin and Chea 2018).

Essential oils, specifically carvacrol, are being explored as antiparasitics (Trailovic et al 2021). This would be a welcome solution to the widespread resistance of roundworms (Parascaris sp.) to all three major anthelmintic (deworming) families.

Generally speaking, aromatherapy uses natural essential oils to enhance animals’ psychological and physical well-being—a broad and sweeping description. As such, these products, which are not and cannot be classified as drugs, are also used for managing painful musculoskeletal conditions, immune stimulation, antioxidant activity, calming solutions, and gastric ulceration. Essential oils can also be administered via inhalation using a commercial nebulizer to improve respiratory health.

Using essential oils in conjunction with, not instead of, modern medicine and with a veterinarian’s expertise, we can:

• Reduce the need for systemic antibiotics. Using products capable of fighting infections without antimicrobials promotes good antibiotic stewardship and alleviates the pressure of creating or treating antibiotic-resistant strains of pathogens.

• Minimize the need for anti-inflammatory medications and their side effects. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., phenylbutazone or “Bute”) might contribute to gastric ulceration or colitis, and corticosteroids have the potential to induce laminitis.

• Maintain intestinal microbiome health. Any medication has the potential to disrupt the delicate balance of microbes found in the cecum and colon. Dysbiosis can result in diarrhea, behavior changes, a compromised immune system, and other negative outcomes.

• Reduce environmental contamination with drugs, drug byproducts, or chemicals.

Just like other complementary and alternative therapies, horse owners tend to consider essential oils universally safe. In reality, the safety of essential oils remains largely undetermined, and both their positive and negative properties need further investigation.

In mice and rats, essential oils are associated with liver, kidney, and reproductive toxicity and changes in blood vessels and can cause oxidative stress (Ebani and Mancianti 2020). Further, a recent series of articles published in the European Food Safety Authority Journal warned consumers to consider essential oils to be skin, eye, and respiratory tract irritants. Human study results report photosensitization following exposure to sunlight and dermatitis after applying essential oils topically. Lavender, peppermint, and tea tree oil appear to be the biggest offenders.

As with joint supplements and other complementary and alternative therapies, choose a quality product. Substandard oils might not contain the listed ingredient at the indicated concentration or amount. Products might be contaminated with other ingredients that can affect your horse’s health.

Finally, be aware of which essential oils equestrian governing bodies prohibit. Be aware some Jockey Clubs and other regulatory sports bodies have included various herbs and oils on their prohibited substance lists, so check before you use if you are competing, especially at a commercial level.

A summary of points to remember using essential oils around animals are;

Always allow an animal to walk away from any application or remedy

Take care around thesensitive areas like eyes, ears, noses and genitals area – avoid essential oil irritants

Understand the extracts you are working with. Read up on how the remedy relates to the species that you are working with

Equines / other herbivores – hold the bottle firmly so that the hand covers most of the bottle, to prevent it from being snatched from your hand and into their mouth

Equines / other herbivores – do not use a nose bag for inhalation purposes

Equine / other herbivores – caution bottles on ledges in the stable; the horse may put one in their mouth. They also may easily be forgotten or fall and break

Cats and dogs – do not use a vaporiser / diffuser unless your cat or dog can walk away from the aroma into another room

This list is taken directly from the work of Caroline Ingram in the UK and you may find her work in zoopharmacognosy interesting.

To get started, essential oils regarded as safe for horses include, but are not limited to: basil, bergamot, chamomile, eucalyptus, frankincense, geranium, lavender, lemongrass, peppermint, and tea tree. Please keep in mind that essential oils are VERY concentrated, and horses are more sensitive than humans. A good rule of thumb is never to put essential oils directly onto your horse without diluting them in a carrier oil or allowing them to float in water if selected by your horse. I have seen a number of horses on box rest for example appear to perk up and be more interested if a few drops of essential oil of peppermint is added to a bucket of water in their stable (extra to their drinking water). I’ve seen horses play with such peppermint water and even drink a whole bucket where they would normally be a poor drinker. If I don’t have any peppermint oil I sometimes make up a couple of peppermint teabags and steep them in a cup of water for half an hour before adding to a separate water bucket if a horse is reluctant to drink water in a new place. By getting them used to peppermint or camomile at home, the water (which may taste very different at a competition venue from home) can be more palatable to the horse.

So long as your horse is comfortable with the smells and reactions in his body to an oil or group of oils you can make up rubbing oils, put oils in water and use a nebuliser to spray fine droplets of diluted oil into the atmosphere around your horse.

Here are some oils and their properties;

Some simple applications are:

Basil

Basil is traditionally used any sort of spasm. It is useful in old and new muscle spasm. I find it particularly useful for rubbing in a dilution in olive oil in show-jumping horses where their shoulders tighten up and in front of the shoulder blade. (The dressage horse and rider might well benefit from a quick sniff of basil before a test, as it sharpens the mind and helps retain focus on the task at hand.)

Bergamot

Bergamot will help relieve any skin irritations. It is useful in addressing mild skin eruptions usually caused by an allergic reaction or insect bites.

(Bergamot is also favourite for dealing with “butterflies’ in the stomach type nerves, so a good whiff might help precompetition nerves for both horse and rider. It eases away anxieties and clears the air so pre-event jitters do not incapacitate.)

Chamomile

Chamomile is an expensive essential oil, but worth every penny. It helps the muscle utilise magnesium so you don’t have the muscles cramp or spasm from intense work. (Camomile is traditionally the ‘tantrum’ remedy in small children and the sleep helper calming and soothing a horse stressed by a situation or struggling to sleep in a new place).

Eucalyptus

Eucalyptus is often regarded as a handy essential oil to have around to ward off winter ills. If you have the scent of eucalyptus wafting around your stable it can act as a negative ion generator. Eucalyptus is best known for and extremely useful as a post-event muscle rub and is included in many liniments. It is also an essential oil that freshens up an environment and useful to have around for horses that are confined in stables for long periods of time as it is supposed to lift the spirits and create a natural feel in the stables.

Frankincense

Frankincense is an old-wound healer and strong anti inflammatory. It can be used in a wash for wounds that are taking longer than expected to heal.

It also helps with respiratory disorders in a chest rub and has some good research possibilities in reducing inflammation associated with both cancer and arthritis. (Emotionally frankincense can be regarded as a good ‘fear’ essential oil and useful if a horse is reluctant to go on transport for example, sprinkling a little diluted in water on the bedding under your horse).

Geranium

Geranium is another oil useful in addressing stuck, aching muscles (I suppose it isn’t surprising that my key essential oils are mostly about massaging and muscles!)

It helps relieve spasms while having a mild analgesic effect so you can massage the muscle more deeply when needed. (This essential oil balances hormones and moods. Some practitioners specifically target this in a massage oil for mares and fillies at times when their hormone might affect their performance)

Lavender

Lavender soothes heat. Useful when addressing inflammation and can be applied gently to bruising and swelling to facilitate recovery. Lavender generally needs less dilution than most oils. (This essential oil will also take the heat out of emotionally heightened situations. When stress is causing disruptions to preparations during a competition, for example, you could have lavender on a tissue or as a perfume to help reduce the stress of your colleague, child or trainer)!

Lemongrass

Lemongrass has an affinity with myofascial tissue and is useful in the recovery of tendon problems as well as shin soreness. (This oil is a favourite to burn at home when learning dressage tests, or to sniff while walking a course the day before a cross-country event or just before a jumping competition. It should help you retain your learning).

Rose

In a 2015study, postoperative children inhaled either almond oil or rose oil. The patients in the group that inhaled rose oil reported a significant decrease in their pain levels. Researchers think the rose oil may have stimulated the brain to release endorphins, often called the “feel-good” hormone.

Based on the outcome of this study, the researchers suggested that aromatherapy using rose oil could be an effective way to ease pain in patients who’ve had surgery. Rose is known as an oil for healing the psyche after trauma and was carried by ancient warriors in Asia. Ancient Persian medicine used rose oil for treating wounds as it has anti-infective properties. You can use the oil topically by diluting it with a carrier oil.

As you can probably tell, I’m fond of rose and I often wear it while working in places where horses I am treating may have trauma, separation, grief or loss in their past as I have found it allows me much quicker access to their bodies for physiotherapy and massage treatments. (For us, rose oil is known to be excellent for the skin due to the antioxidant activity of rose essential oil, which spurs on the natural healing processes of the skin – so having a little rose in a rubbing oil for your face might brighten your appearance when showing!)

Tea Tree

Tea tree has traditionally been used by aboriginal horseman in Australia, brushing the branch of the tea tree bush across the back of an itching horse. It is useful in a blend of essential oils for rain-scald or fungal infections like ringworm, as well as in a wash for wounds to prevent infection. But take care to dilute this oil as it can cause a reaction in some individuals.

I’ve mentioned diluting and massaging with oils; Essential oils affect horses psychologically and physiologically when used for massaging. When making up a rubbing oil, the recommended dosages applied to humans suffice for horses. A rule of thumb is 100ml of base oil to carry 2.5ml of essential oil. Choose the type of essential oils to use, determine how many drops it takes to make a milliliter, and then begin to blend your massage oil.

You may incorporate the blend in a style of massage you already use or you may use it as a spot liniment.

Essential oils absorb through the skin via the hair follicles as their molecular structure allows them to pass between the dermas and enter the body’s extracellular fluids. With this in mind, your massage strokes are long and sweeping, warming the body and hastening up the absorption of essential oils. If you find an area of muscle resistance, you may concentrate your techniques there, always remembering to resume the original intent of your massage.

It may take as long as a week for the body to absorb and metabolize the essential oils and excrete them out through the urinary system.

Please remember not all oils are made equal and look into buying organic oils from a good brand. They are more expensive but worth the money. Some brands offer advice sheets specific to horses too so it is worth checking out the brand online and seeing what you can learn.

Just to get you started on massage with essential oils;

Getting Started: A blend for sore and tired muscles

Rosemary 10 drops

Bergamot 4 drops

Juniper 6 drops

Lavender 5 drops

Essential Oils page 2

This blend will improve circulation to muscles and relieve anxiety.

*If the dropper dispenses 40 drops to make a ml., then use 25ml of cold-pressed vegetable base oil.

Again (sorry I am labouring the point) – Never use essential oils straight out of the bottle. They must be diluted with a base oil.

Let me know if you have tried using aromatherapy with your horse. Have you engaged an aromatherapist or aromatherapy practitioner veterinarian?

The body as a whole body when helping your horse

Fascial connections we rarely talk about are the ones inside the thoracic cavity!

Sometimes we struggle with the horse’s body and even when we do everything right the horse is still unbalanced.

This can be because the musculoskeletal structure can mirror the visceral restrictions in the body. Ie. the nerves, circulation, organs and internal structures that carry old tightnesses, scars and adhesions.