A difficult horse

‘Maybe keep this one on two ropes – he can be a little tricky’ (at least this is more honest than the admission that ‘ah yes he did bite and kick the last one’ or even ‘my goodness I’m amazed she went in with you after the awful trauma she had in a stable – she has reared near each stable for the last four years!’ – I’ve heard those and many more)

Now I very very rarely work with a horse on a long line when I am doing bodywork, rarer still tied up and occasionally because of the set ups in yards and training establishments I have no choice but to work with a horse ‘cross tied’ which means a rope attached to both sides of their head collar.

Ideally I want them to be as free as I can have them within the constraints of time (i don’t always have the luxury of waiting for hours until they are accustomed to my being in their presence on a visit – though I do have the facility to do that at home if they come to stay in my little herd of ponies for their rehabilitation).

I will often start with a first session by introducing myself while the horse is help on a rope by the owner, using advance and retreat to let them see the kind of touch and how my machines might work and (importantly) giving them time to process and say yes or no. I often work with a horse loose in a bald stall and go away to the corner to give them space to process what I am offering.

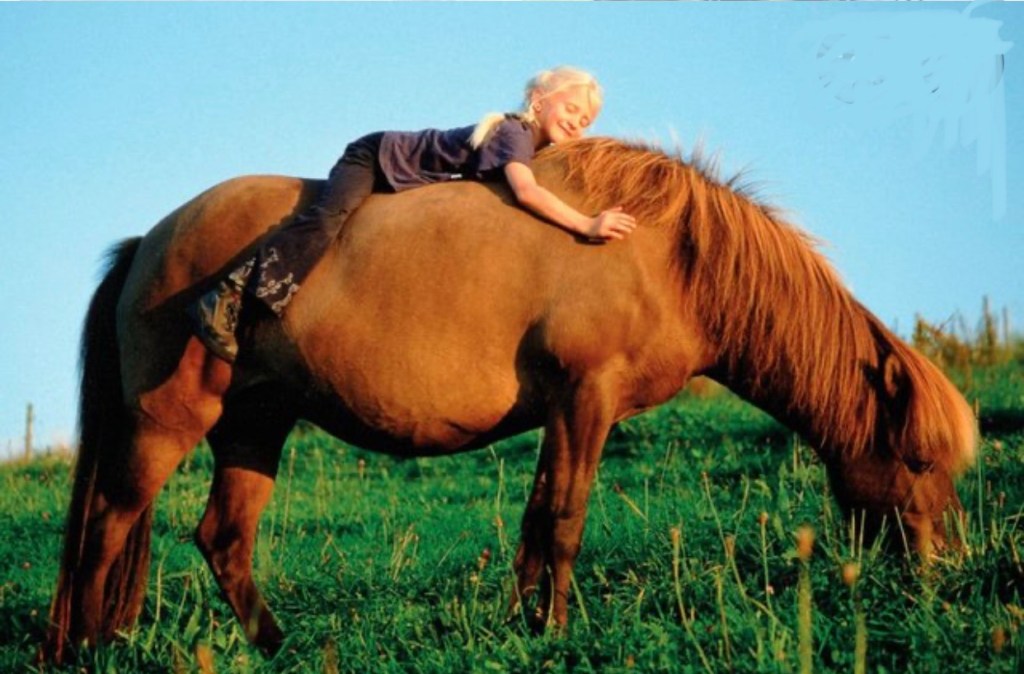

My favourite way of working though for massage and light touch Ki-Equine technique is to be loose in a paddock or shelter barn with the horse and his or her friends. I love doing this at my colleague, Jolande’s Hästgård Mosjö Stall. Her horses have a lot of choices in their lives, despite being in a western riding Center with both lessons and trail rides and this freedom and herd life shows up in their acceptance and conversation around any bodywork I offer.

It is the reason so many of the practical sessions in the Svenskafysioskolan’s base level horse fysio course. (The wonderful thing about equine bodywork is that you can be constantly learning and adding to your earlier techniques from both courses and by learning from the horses we serve).

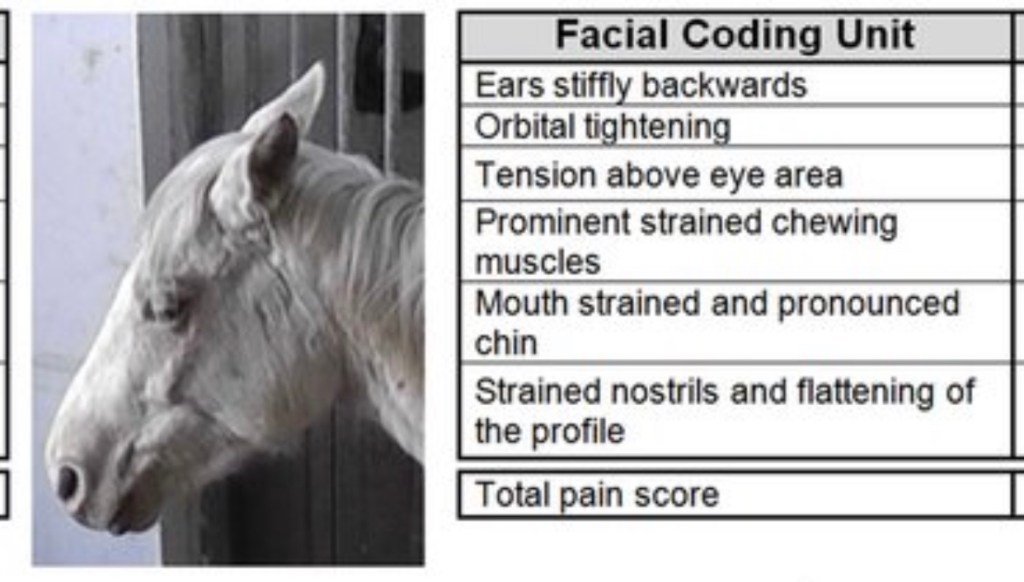

Learning to listen with our eyes and energy as equine bodyworkers is as important in my view as learning all of the anatomy and physiology that is essential to understanding what we do. Self awareness is essential and giving horses choices as far as possible is best practise.

But what does it mean to give your horse a choice.

My job is to communicate as clearly as possible what I have to offer or what I want the horse to do (sometimes my treatment may be less comfortable than the horse would like – think of changing a dressing or gently stretching a very tight and strained muscle) and give time and space for a ‘yes’ or a ‘no.’

This is obviously easier if I am working regularly with a horse rather than visiting for a one-off treatment but it is possible in that setting too.

In fact giving our horses choices and a little more freedom within their domestic (captive) lives is a wonderful partnership exercise and not just for bodywork.

It is worth asking how much freedom you actually give your horse. And also how you could extend those freedoms.

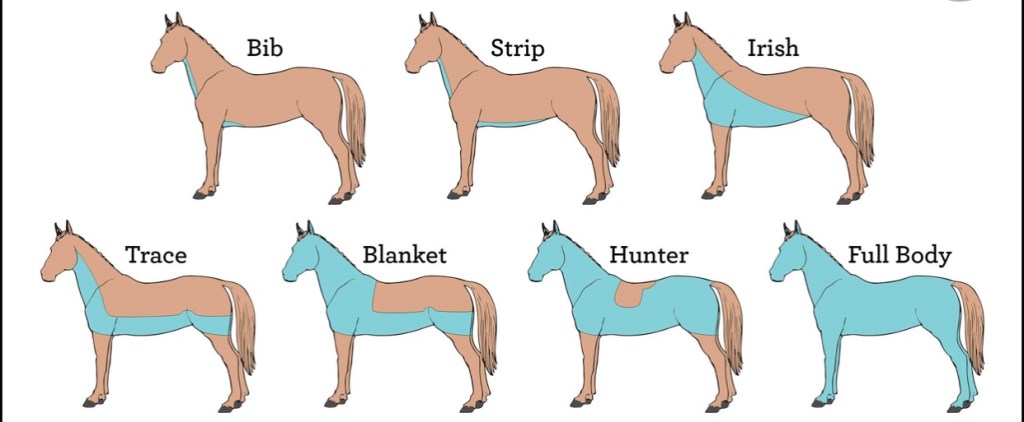

We often curtail freedoms ‘for their own good’ or for our convenience. A fluffy horse gets too hot and sweaty when worked so needs clipping (for our convenience) so needs a rug and the constraints to his movement and natural interaction with other horses that entails (mutual grooming isn’t the same through a rug). I am not suggesting that you don’t clip or don’t rug your clipped horse but more that you think about what freedoms you take away and what you can offer.

A horse that has space to move and friends to move with will be expressing more of his natural behaviour than one alone or who spends considerable time in a stable. Is it possible to offer a shelter and space to move as much as possible instead of individual stables or boxes in winter, for example?

I have to limit my little group of six ponies and horses in winter as my electric fencing doesn’t currently (yup another of my awful puns) stand up to the unintentional attacks of enthusiastic elks and I don’t fancy walking the miles in the deep Swedish forest snow following where my horses might wander if ‘let out’ by a friendly moose! But I can try to offer them a slightly more interesting life with slightly more choices than simply standing in a small paddock and eating a large bale of hay. I have a ‘ligghåll’ (a large shelter barn that easily accommodated them all loose and which can be shut at night if I am nervous of the local wildlife or for weather based emergencies) and a fenced track with a wooded area for them to take shelter and explore the hay piles I drop there (in different places every few days). It isn’t ideal and if I win the lottery I will drastically improve my fencing in one go (rather than the rather slow process I am attempting annually just now) and give them a much bigger and more interesting area.

It is the most freedom I can offer them within my own limitations and that is what I am considering in this blog post.

I don’t suggest we all have the possibility of letting our horses range over miles of land in the freedom and constraints of a herd of wildings but each of us can look at the choices and freedoms we can offer our horses today.

This allows us to develop healthy partnerships rather than a ‘Lord and serf’ or worse ‘jailer and prisoner’ kind of relationship.

I’m guessing nobody reading this blog is interested in dominating rather than cooperating with their horse?

And yet I commonly hear and read so much talk of ‘being the leader your horse needs’ or ‘taking control.’

I have to be honest and say these are phrases I’ve used in the past when giving riding or horsemanship lessons. I’m not suggesting that the opposite is the right way forward either. This is not a proposal that you should become a stablemat walked all over and used as a toilet for your horse.

No what I am aiming for nowadays with my horses and those I serve as a rehabilitation therapist, trainer or bodyworker, is a partnership.

I learned a lot from Luki, my horse of a lifetime, that others described as the ‘hell horse’ (unbeknownst to me before I bought him).

He was in fact the most delightful gent with an open, honest and forgiving nature who taught me to listen to his communication with an enviable patience! Over a good few years (I am a slow student) I learned to sit still and wait if he stopped abruptly along a narrow Shropshire lane (saved from an out of control coach, several lorries and overly speedy motor bikes none of which I heard coming); I learned to get off when he was older and stopped and dropped his head, walking by his side instead as we explored parts of the countryside I had missed by going on the routes I had previously chosen; I learned to trust him when working with children with disabilities and to watch his responses for my therapy; I learned that he offered inordinately good friendship and even leadership if I would let him. And as I learned those things I also learned I could ask for his trust at the times when I needed to take the lead.

Luki taught me to be a partner not a leader. I am so thankful to him for his patience as I very slowly tried to learn my lessons and try out different forms of horsemanship over the more than 25 years we were together.

The other thing about a partnership like that is just how much you miss your partner when he is no longer around. I am so grateful for his memory, though.

Giving our horses choices seems like a tough but nice idea – but it comes with conundrums;

What about if you need to deliver medicine or wormer – how can you offer choices?

Can you demonstrate what is involved and take the time to allow the horse to come to the conclusion that cooperating with you in this would be interesting.

If you are training with a technique which offers positive reinforcement (like clicker training, for example) it is important to offer another choice (which is not a difficult or uncomfortable experience) so that the horse can make a real choice and not simply a ‘no real option choice!’

An example of this would be target training with a clicker towards taking a wormer. You could have an amazing and highly desirable treat as a reward for moving nearer the working tube. But what if you had a good source of relatively nice hay or fodder nearby… then your job is to make your own reward and activity interesting enough to get a ‘yes’ from your horse. But it is also to accept that your horse might say ‘no’ today.

It doesn’t matter what we are doing with horses or what method of training we use, getting a good response and real learning is going to take the time it takes for this particular horse in this particular setting. Rushing and forcing might get you a quick and ‘successful’ result in the short term but it probably won’t result in the horse learning the lesson you needed him to learn in the longer term.

When I have worked with the ‘difficult to load’ horses over the years I have often seen how just such a forced ‘ok then,’ from a horse has eventually resulted in a ‘heck no,’ for the future with sometimes extremely dangerous results to both horse and handler. The result has been a need to go right back to first principles and offering choices in which the horse is calm enough to learn. In the past I have followed the make the wrong thing hard and the right thing easy method but I now try to follow ‘make the right thing fun and interesting and accept a no as a time to take a break and go back a step or two’ approach. I am being pleasantly surprised by the speed of my results-

It seems like when I add the choice to take time away, to say ‘no’

…..and the time for me to rethink my presentation of ‘my idea’ so that it might be more fun or more interestingly clearer….

It seems like the learning (on both our parts) goes quicker and with a lot less stress (for me as well as my equine friend)!

In a future blog I will talk about sensory learning and how the cortisol cycle can adversely affect the outcomes we would like for our horses (or dogs or kids for that matter), however for now it is sufficient to say that calm horses who have the knowledge they can say no if they need time will lead to partnerships that allow you to get a ‘yes,’ when you need it (in an emergency or during a veterinary procedure for example).

If I take the time today; tomorrow the job will probably take half that time and so on……

I would love to hear from my readers how you offer choices to your horses. It is a great way to get ideas! The more we can share our examples, the more choices our horses and other horses can be offered…..and the better the chance we have of developing healthy, happy horse-human partnerships.

My new year resolution as I go into 2022? I’m going to keep looking to add choice into my training and therapy as much as I can